Until July last year, I was working as part of NHS England. My position arose not out of professional choice on my part but in light of the seemingly endless merger and acquisition activity that takes place amongst the arms length bodies that exist in and around health and social care.

I had originally joined the NHS Leadership Academy, which was at that time hosted by Health Education England. The Academy was then spun off into NHS Improvement – specifically the Trust Development Agency, which represented one of two parts that had been awkwardly yoked together in that organisation.

Thereafter, NHS Improvement was swallowed whole by NHS England, the latter coming into existence in response to the Health and Social Care Act 2012, often referred to as the Lansley reforms, which on reflection can be seen as a centralising exercise defined largely by crude neoliberal managerialism. NHS England had no real purpose outside of mitigating the flaws in Lansley’s model.

More recently, NHS England has gobbled up both NHS Improvement and Health Education England to create a weighty monolith that sits on top of the service.

Whose values?

At a time when senior leaders place so much importance on corporate values – primarily because it is one of the epiphenomenal issues on which they feel bound to focus, given their distance from the business of the business – it was intriguing to see how people were unthinkingly moved around in light of all this M&A activity.

The notion of values was largely disregarded when people in the upper tiers were concentrating on squeezing together organisations to meet a structural as opposed to a systemic agenda. That said, values did appear in circumstances where change processes were introduced, when there arose the expectation that the workforce needed to be shuffled around. In such instances, the shift from a strong focus on the fairness of competence based recruitment to the vague notion of getting people to show how their practice mirrored some vague and imprecise values was rapid indeed.

This fluidity reminded me that ultimately what matters is not the extent to which people can persuasively demonstrate that they live the values of the organisation – a meaningless and performative exchange that persists in bureaucratized HR practices – but rather the personal values that people bring to work and which prompt them to do their jobs to the very best of their abilities.

In the space of a few years, I was bumped between organisations, on each occasion landing in a new corporate context replete with its own set of values. (Often, these were deliberately confected by the senior leadership in light of the merger itself.) However, in terms of values, the only consistency were those that motivated me to do the work that I did to the highest possible standard.

Contested corporate contributions

It is actually the case that – in light of changes that were going on – I reached a point where my values felt compromised by the organisation in which I had landed. It was difficult to discern what value NHS England was adding at a time when the frontline services were struggling to juggle the circumstantial challenges and the developing ambitions for the NHS.

Structurally, there was an evolving sense of redundancy for NHS England, given that the introduction of Integrated Care Systems had largely erased the elements of the Lansley reforms that the organisation had been established to check and balance. Moreover, given the existence of 42 Integrated Care Boards, it was unclear as to what NHS England’s contribution in this new structure was meant to be, given that it was now somewhat redundantly sandwiched between the Department of Health and Social Care and the range of ICBs.

Doubtless it was a recognition of a tier that was duplicating work that took place above and below it that prompted a professional services company retained by NHS England to recommend reducing its workforce by 40%. In terms of that target, it was reported just a few days ago that the organisation had been reduced by 7000 posts, roughly equaling 30% of its workforce, with a suggested overall cost of what was glibly described as a “transformation” of around £75m.

There are many dedicated people trying to do effective and impactful things in that organisation. But their values and competence could usefully sit elsewhere, in recognition of the fact that there is an urgent need for a radical reconfiguration. This was clearly stated in a recent report by Reform, a public services think tank, entitled Close Enough To Care: A New Structure for the English Health and Care System, wherein the following recommendation appeared at the very beginning of their review:

‘The Government should commit to phasing out NHS England as

quickly as possible. The Department of Health and Social Care should take on NHS

England’s remaining specialised commissioning functions, as well as responsibilities for

setting core service entitlements, monitoring high level outcomes, determining resource

allocation, and providing high level strategic support.’ (p6)

This follows on from a somewhat critical review by the National Audit Office of NHS England’s modelling, which it used to craft its recent much heralded Long Term Workforce Plan. And similarly NHSE published a leadership framework recently, which prompted me – in light of my experiences – to mentally revisit the Biblical adage, “Physician, heal thyself!” Although, that said, I am unconvinced that the panacea, created off the back of a report on leadership in our health service by a superannuated military officer that lacks any creativity or a single innovative thought, could offer any meaningful remediation to a dysfunctional and poorly led organisation.

Structures and Systems

The persistence of NHS England despite the significant change in circumstances reminds us of how we remain transfixed by structures. We continue to fetishise the organisational chart, even though it actually tells us little more than what inflated job titles people carry in that context and roughly what the organisation pays them for occupying that role.

Far too many efforts at organisation design engage in this focus, to the extent that Naomi Stanford, a thoughtful theorist and practitioner in this field was observe the following in the second edition of her seminal work on the topic:

‘A reorganisation or restructuring that focuses – sometimes

solely – on the structural aspects is not organisation design and is

rarely successful. Ask anyone who has been involved in this type of

reorganisation and there will be stories of confusion, exasperation

and stress, and of plummeting morale, motivation and productivity.

Most people who have worked in organisations have had this

experience. So why is it that initiatives aimed at revitalisation, renewal

and performance improvement so often miss the mark? The simple

answer is that focus on the structure is both not enough and not the

right start-point.’ (p5)

Occasionally, we see the reckless embrace of structural change, which is invariably focused on making significant changes at the bottom of the pyramid. Rarely do we see a similar rash pursuit of structural change at the peak of that pyramid. The top is always left untouched, even though the peak relied intrinsically on the base for its position.

Ultimately, though, the fascination with structure distracts us from that which goes on below that artificial surface in those social spaces where people come into contact with one another and find ways in which to get things done. Very often, those ways in which things get done stand in sharp contrast to the structures, the supposed blueprints for how things should get done.

Structure is the space where people who define themselves as leaders live, where they end up focus endlessly focused on ethereal notions such as visions, missions, and values. It is the space wherein we intimately experience hierarchy and a crude division of labour, where we are enticed into giving voice but where silence is the safest position to assume. In organisational structure, we can see the castle on the hill, overlooking us all in our contemporary serfdom. Structure is where modern-day neo-feudalism resides.

Meanwhile, the system sits beneath this artifice, experienced as a network wherein people connect to get things done, where the focus is very much on the production and delivery of the goods and services on which turnover and profit depend. It is where leadership as a living practice presides, a way of being instead of simply knowing and doing – and one that is intrinsically fluid. It is where people informally connect to smooth off the elements of the structure that get in the way of efficiency and effectiveness.

In the structure, it is assumed that values have to be imposed on people. They seek to prescribe how human agents engage with the challenges of coming together socially to get something done. In the system, the values accompany those who step forward to connect with others to deliver what’s needed – and arise out of the day to day connection of those people, whilst being under constant review through the lens of actual practice.

These, then, are values that give shape and direction to how things are done as they are planned and actually done, as opposed to the corporate values that in truth look to tightly manage the human soul. To call these values is a terrible misnomer: they are ideological tests and constraints in terms of human agency. They serve the needs of managerialism, not of practical and active management.

“No Future in England’s Dreaming”

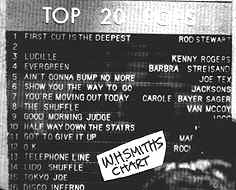

So sang the Sex Pistols back in 1977 in their song God Save the Queen, a record so provocative that WHSmith refused to include it as part of the Top Twenty chart that they displayed in the record department of all of their stores, despite the fact that it reached Number 2, as you can see from this picture.

Despite the constant use in the world of business of rationality as a touchstone, a good deal of corporate life resides in a self-referencing context, which is notably distanced from the practical realities of the wider workforce in that organisational context. This is the dreaming that shapes and sustains our working lives, a state that arises out of the focus on structure as opposed to system and which preserves the organisational period for no good practical purpose other than to sustain extant power relations at work and beyond.

What if an organisation wanted to wake up from its dream-filled slumbers and acknowledge the systemic as opposed to the structural? Karl Weick’s distinction between organisation and organising would need to be explicitly acknowledged in every corner of the workplace – and, in conjunction with this, there would need to be an acceptance of Harold Bridger’s discussions about how organisations encapsulate a primary task – the practical work of the business in terms of delivering its outputs – and a double task, which is a way of considering the group dynamics, often largely hidden away, that underlie the delivery of that primary task.

Bringing together these two perspectives on organisations and our experiences in them allows us to start to explore our connected lives in the workplace at a far deeper and more critically oriented level. This requires us to move away from the fixity of the two by two matrix, so favoured by management consultants in terms of guiding their clients to a specific remedy…which they just so happen to have developed. Instead, this analysis assists us in appreciating the dynamics of where we work – and the tensions therein, to which we might usefully give some attention.

Our corporate lives feel dominated by a constant focus on the short term immediacy of immersing ourselves in delivering goods and services. From a senior leadership perspective, there is also a seemingly eternal hunt for new ways for this practical work to be undertaken, which leads us to the fascination that was previously noted with structural issues. This tight focus regrettably displaces discussions that could take place about why the present focus prevails. Similarly, it denies the existence of the conversational space wherein people find largely formally unacknowledged ways in which things get done.

It might be argued that the managerial obsession with corporate values represents an attempt by people who are notionally leading organisations to intervene in the double task, rather than acknowledge it and then take the time to support a rich and meaningful discussion up, down, and across the company about it.

The value of values that we hold personally is that they motivate us to do the work that needs to be done and to do it to the best of our ability at the very highest quality. However, the imposition of anodyne yet compulsive corporate values is intrinsic to what Carol Axtell Ray describes as a third stage of managerialism, a phase she describes as culture control. And, for most organisations, engaging with their workforce to invite them to describe the values that they hold at a personal level would be a useful starting point for a more connected and conversational corporate context, rather than one that thrives on control.

It would be the first step in respect to moving away from an exclusive focus on the structural in order to engage with the systemic, the better to understand how things get done in your company – and what people really think about working there.