Why there’s no fear of free speech going too far

By John Higgins and Mark Cole

First the fantasy. What if the people who came along to our recent sessions, promoting our book, bristled at our advocacy?

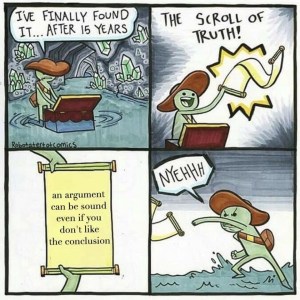

We were/are committed to the need for silenced voices, even those we’d prefer not to acknowledge, to be heard and understood – rather than judged against a fixed ideology of truth. To rework Elvis’ work, what we want to see is “A little more understanding, a little less lecturing, please”.

But the audiences at these four very open and conversational events, made up so we thought by the committed, the open-minded and the simply curious, didn’t register a single objection. No one challenged white middle-aged, posh John as he spoke of how he had come to terms with the need to hear from a white, middle-aged bloke, who was angry at being discriminated against because of policies around gender and race. No one said: “I don’t want to give a racist [sexist, insert pejorative label de jour] airtime”, although it’s a kneejerk reaction both of us innately understand and with which we have some sympathy.

Mark has spoken elsewhere of his experience as an undergraduate at the University of York, when the campus Conservatives invited Roger Scruton to speak. Mark was perplexed when more open-minded Labour Club comrades eschewed the sloganizing hordes outside the lecture hall one evening and instead joined the audience so as to hear what the professor had to say.

Meanwhile, Mark made common cause with those who sought to deny a platform to a thinker who took a markedly different view of the world to them. There was no sense that anyone in the hall, particularly Scruton, would be influenced by the chants of the demonstration outside. It seems reasonable to assume that the unspoken purpose of this expression of voice was merely to disrupt the experience of those in the hall.

At the end of the event, the campus authorities arranged for Scruton’s car to pull up some way away from the lecture hall so that he might leave safely via a back door. Mark and those with whom he was making common cause cottoned on to this…and charged over a greensward towards the hastily withdrawing speaker.

This was not mere disagreement. It was leagues away from debate. It was instead an attempt by a mob to silence someone who was not one of them. In one of his books, Scruton makes mention of how discomforted he was by this experience. Mark carries the shame of that experience to this day.

Using voice to create silence

What the above speaks to is the desire, or expectation, that one group has the right to silence the voice of another group. The belief in the rightness of a cause permits any unbelievers to be purged from the public sphere – which doesn’t just echo, but directly parallels, historic and persistent attitudes in many religious traditions. Silencing heretics has a long, violent and intolerant track record.

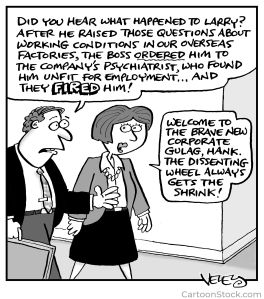

The corporate conversation has also become an ideological space informed by habits of religious intolerance. In many places it is a sanitised, policed space of reactionary radicalism, where one-group’s view of truth is ruthlessly turned into an enforceable norm. Differences of opinion are labelled not just wrong, but BAD, and sometimes taken out of the rough and tumble of politically informed difference by being called out as an ILLNESS (a phobia). To not see the right truth in the right way means that you must be sick.

This pathologisation is what Michel Foucault highlights in his nuanced perspective on the conjoined relationship of power and knowledge, which he sees as only existing under the inseparable title of power/knowledge. In this perspective, the development of a way of knowing the world leads to a definition of normality…and, in contrast to that, to what might be seen to be the ‘Other’. Knowing creates norms which define in-groups and out-groups, which in turn sustain the boundary between what is normal (and right) and not-normal (the heretic, abnormal, wrong ‘Other’).

In this conceptualisation, power becomes internalised; it does not so much act on us, as act in and through us all. The example Mark offers in his Unpacking Power sessions is that of introversion and extroversion. In the corporate context, these two positions cannot truly be said to have a parity of esteem. Everything in organisational life seems to privilege the extrovert.

Meanwhile, the introvert is castigated for not speaking up enough – and may be threatened with a so-called development course that will supposedly build their confidence. The extrovert is rarely directed towards a programme to teach them to keep their counsel, dial down their voice, and surrender some of the airtime to others.

Extroversion is seen as the normal, perhaps even the natural, state…which in turn Others the introvert in a way that can seem to medicalise their personal disposition and choice to listen more and speak less. This, for Foucault, is the way in which we experience power acting on us all in contemporary society.

But for power to manifest, it is suggested that there must be resistance, a religious canon needs its heretics to define the boundary between what is canonical and what is heresy. And so counter-narratives take root in secret, creating subversive sub-cultures which appear compliant to the paraded orthodoxy, while going about their daily work with their subversive take on the truth uncommented on and unchallengeable, because the words to express their truth do not exist within the canonical truth. Canonical truths inevitably atrophy, devoid of liveliness, with all energy invested in policing their rightness and persecuting unbelievers.

The corporate discourse has the qualities of such a canonical truth and is dying as a source of liveliness and human connection, replaced by an iron hug of tyrannical pseudo-niceness and an assertion of world views many would like to take issue with… if only there was somewhere they could go to be honest with others.

How did we get here?

Let us present Exhibit A – a corporate ‘value’ from a renowned global educational institution. It evaluates all of its employees against the phrase: “Show’s a killer instinct”, or words to that effect. This presents an immediate challenge to the two of us. Do we want people who teach and counsel the young to be killers? What if the two of us were among the throng of people invested in the sanctity of human life or the Biblical instruction to “Not commit Murder”? Should we look to save the immortal soul of this institution from eternal damnation? Should we sue the institution for corrupting and imperilling the souls of those good people it employs?

Corporate ‘values’ are an example of enforcing a particular world view on others – they are ideological weapons to police the voices of others, drive out reflection and conversation in preference for compliance (or at least its simulacrum). They create a particular climate of silence.

No one seeking to join an organisation is invited to share what their personal values might be. Leaders eschew such personally held values (which have the potential for heresy), that motivate people to choose to work in certain settings and do their work to the very best of their ability, because these exist at the level of the ethical self…and the one thing that contemporary corporate life is eager to steer well clear of is ethics (except as another auditable regime of demonstrating compliance with the approved of corporate game). Corporate values are mere agitation and propaganda to support the organisational regime…but the fact remains that by and large most people are untouched by them and barely register them as part of their working life.

Then comes its close cousin, the world of behavioural matrices against which people are to be assessed; presented as a tool for fairness, they reveal meritocracy to be what it actually is – an exercise in what Arthur Koestler called rattomorphic control (p560). By creating a moral norm that all are to fit with, they create a diminished emotional and intellectual space for people to connect in. Why wait for AI to turn us into robots, when competency matrices (turbo-charged by ‘values’) are already doing an excellent job?

Finally, from the outside world, comes the intolerance of activism, which the corporate realm is happy to institutionalise as it fits neatly with a world of singular, absolute truths. The corporate landscape loves intolerance because it fits within the language of control and managerial fiat. Businesses are, so the popular discourse says, hungry for certainty. The activism that will be tolerated is that which sits comfortably alongside the marketing strategy; that which will be silenced is anything that contests the corporate status quo, questions the leadership of the organisation, or offers an alternative way of imagining the workplace.

What is to be done?

The temptation is to say: “I wouldn’t start from her”, and such a wish points to a serious conclusion, which is that we (as people who live in a corporatized theocracy) need to start dismantling the stultifying habits of a corporately shaped life.

There is a Latin phrase, “Cui bono”, which can be loosely translated to mane: “Who benefits?”, and is a good question to ask when looking at the current way conversational life is conducted within our workplaces and wider society.

So who benefits from a world of carefully crafted values imposed from above and which silence the personal and wider community ethics of people? Who benefits from sustaining an orthodoxy in which differences are ignored or purged?

The first beneficiaries are the narcissists who wish to see the world as a reflection of their own fantasies – so our first action needs to be to call out narcissism for what it is (and stop genuflecting to the preening self-regard of Mr Musk et al).

The second beneficiaries are the bureaucrats, those who believe that the world can be codified into correctness. Our second action is to call out the life-killing consequences of standardisation and categorisation. That feels like a good enough starting point – and is a form of creative destruction that is good for the human spirit, rather than the creative destruction which seems to satisfy only the needs of the narcissists and the bureaucrats (who are always on the lookout for a new form of liveliness to codify and kill).