The National Health Service in the UK (NHS) echoes with corporate messages about valuing the voices of everyone who works there…but this is a hollow sound in light of the failure of so many people who are notionally in charge of our services to pay proper attention to what people are saying — or, in so many cases, not saying, as they opt for silence in an environment that feels hostile to those who say something.

As I write, the annual NHS staff survey is launching again, with people being invited to “Have Your Say“. This blunt instrument will condense the experiences of those who respond to a crude array of numbers, as it is the ultimate exercise in looking to crush the complexity of human experience into a spreadsheet.

This is an anonymous and voluntary activity that many NHS staff hold in utter disdain, in light of the fact that they know that, year after year, they complete the survey, only to see nothing happen in response. I recall taking the results one year to an executive team meeting and, in introducing the agendum, the CEO observed that there were “no surprises there”. No one around the table seemed concerned that they had presided for 12 months over a situation that looked unchanged.

Most top teams receive the material and then demand that someone crunches the data to make little league tables: How are we doing in comparison with NHS organisations local to us? How are we doing across the region? How are we doing in our sector (i.e., mental health, acute providers, etc.)? The extent to which this is anything to do with having one’s say remains moot.

Over the coming months, people in the corporate functions – in particular, HR and Communications – will be compelled to ceaselessly promote this vacuous exercise, investing huge amounts of effort to compel people to reluctantly complete and submit the survey. I have recalled elsewhere my experience of working in an HR department that was at short notice set a KPI target of achieving a 55% response rate across the Trust where I worked. My colleagues and I literally turned up in service areas in order to cajole people into filling the survey in there and then. Considering it’s meant to be anonymous, staff were naturally suspicious as to how the dreaded HR knew that they hadn’t completed it.

This to me is a prime example of a gap between espoused theory and actual practice when it comes to voice in the NHS. The leadership talks the talk…but no one else in the organisation truly gets to talk. I consider this expensive exercise to be camouflage: the appearance of listening disguises the fact that attention is not truly being paid to what is being said.

Free to speak up — and free to be ignored

The Freedom to Speak Up (FTSU) initiative in the NHS looks at face value like a positive step forward in terms of encouraging people to say aloud their concerns and ideas.

Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of those who work as FTSU Guardians in NHS organisations, the process has quickly become bureaucratised, with the managements of those agencies speedily sending it down a measurement cul-de-sac.

Those Guardians — often expected to pick up this responsibility alongside their substantive roles and with nothing like the sort of facility time that might be granted to a staff representative — find themselves all about the numbers, with FTSU cases absorbed into a process of superficial tallying, with the Guardians rarely having the time and space to look systemically at the issues that are arising across those caseloads.

Importantly, this initiative seems to have done very little to change the context in which people find themselves in respect to being heard. The expanding number of cases no doubt reflects a greater willingness of people to bring things to the attention of others — but it also suggests that the need to use these channels through which to speak is in no way diminished. Quite the opposite, in fact.

This looks to mean that the embrace of the notion of Freedom To Speak Up has not seen a change to the practice and culture around employee voice. If people felt free to speak up, they would not be doing it through Freedom To Speak Up arrangements, grafted onto the corporate structure.

Let me share with you here a recent experience that seems to indicate that the NHS is unchanged by the continued presence of these arrangements. Indeed, it can be seen as evidence that extremely poor practice in terms of staff engagement is being hidden behind the notionally reassuring FTSU superstructure.

Speak when you’re spoken to

On a recent online staff event in the NHS, I noted the presence of someone carrying the title “Moderator”, who was clearly deciding which of the questions from the audience were being allowed to appear on the Sli.Do channel that was being used. I decided to ask this person — whomsoever they were behind the title — as to what criteria they were using to moderate the discussion. I was reminded of a recent re-reading of Kafka’s The Castle when an answer eventually appeared, which suggested that they were too busy moderating to be able to tell me how they were doing it.

Later in the same call, a bland HR reassurance was offered about trade union involvement in a consultation process that was about to launch in the organisation. I was aware that staff representative organisations had taken a dim and decidedly critical view of work that had been undertaken in advance of this, although there was little or no evidence that their concerns had been heard, let alone acted upon. As a result, I queried the extent to which we could be reassured that the Trade Union voice would be properly heard in this next phase of the process.

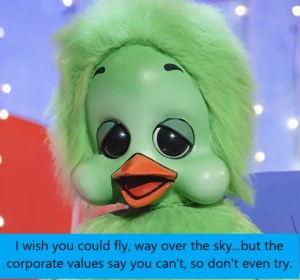

The “Moderator” replied directly to me in light of my decidedly anodyne but pertinent question and advised that they were only accepting questions that had been drafted in the spirit of the NHS corporate values (which I was pretty certain had been the case for me putting forward this query). This is a reminder of the totalitarian potential of corporate values, something that often seeks to deny a diversity of voices in favour of an homogenised managerialist view of the world to which everyone is expected to subscribe (apart from those in the organisation invested with sufficient positional power to be able to disregard it with impunity).

I raised this with the two Board level FTSU Guardians: having resent the message twice, I eventually received a bland holding response from the Executive…while the Non-Executive Director who held this brief never deigned to even acknowledge that I was raising an issue. I shared it with the FTSU Guardians for the area of the organisation in which I worked. One advised me not to make too much of an issue of it, in light of the changes that the organisation was about to embark on; another offered me advice as to how I could have redrafted my question to make it acceptable to the anonymous functionary whose role now looks to have been to render workforce responses to the managerial agenda more moderate and more corporately acceptable.

Eventually, the case was “logged”, thereby being pulled into the metricised madness of corporate life by bolstering the numbers set against a completely meaningless key performance indicator (KPI). But nothing actually happened about it. It was sucked into the lifeless heart of the organisation and lost for ever, the only vestige of it being that it was registered as part of the FTSU caseload across the agency.

Listen to hear; hear to understand; understand to encourage dialogue

My experiences lead me to conclude that the annual staff survey and the FTSU initiative doubtless arose out of good intent – but have both assumed an ideological complexion now, which allows leadership across the NHS to say that they’re listening – but what they actually want at heart to hear is their own positions and opinions coming out of the mouths of others.

These circumstances have not been deliberately designed. Instead, the complex weave of circumstances faced in terms of trying to manage the delivery of truly effective health and social care interventions have led them to become distorted.

There is a need to return to first principles: if you are a leader in the NHS who is serious about allowing people around you to give voice; if you are interested to actually hear about the experiences of those people, and if you are deeply concerned that the structure that you and those around you inhabit and serve to reproduce is deliberately or inadvertently silencing people, the opportunity to embrace “change” – not as something done to others but as something at the heart of your presence in the workplace – is there.

And there are people – including both me and my colleague John Higgins – who will be happy to come alongside you to offer support and guidance as you look to step into that space.