Who doesn’t like having fun, eh?

Well, that’s obviously a somewhat loaded question, subtly but perhaps unintentionally structured to “lead the witness” to a particular conclusion. Surely, it intimates, everyone likes fun, right? Unless you’re just an old misery-gills. In truth, though, the answer people offer will surely depend on the personal perspectives of each and every person that you ask and their individual circumstances at that time and in that moment.

Their replies may reflect them taking a line of least resistance, moderating their voice and opting to silence some of what they might say in a different context. This will particularly be the case in an environment undergirded and overwritten by power, such as the workplace.

Similarly, the discussion is likely to be overshadowed by considerations as to who is defining what is “fun” and why they are mobilizing it in this specific instance. Underlying this is a deeper consideration as to why “fun” has emerged at this particular time as something that is important and how it is presently manifesting.

Workplace Power

When the workplace starts promoting the importance of “fun”, it is worth hitting the pause button to see how power might be present at that moment in the social fabric in which we find ourselves. In a corporate setting, someone might be using their positional power in order to shape practice and behaviours of others in that context. At a more nuanced level, a climate might be emerging across the workforce that privileges the particular notion of “fun” that has appeared in a certain circumstance.

The traditional notion of power sees it as something possessed by someone by virtue of the position accorded to them in the hierarchy that is firmly established. Hence, historically, a queen or king by virtue of an accident of birth and an ideological conceit that said that their power derived directly from God could punish, torture and kill any one of their “subjects”.

Contemporary understandings of power, however, acknowledge how a constellation of social changes in the immediate pre-modern period – industrialisation, urbanisation, democratisation – meant that arbitrary and absolute power would no longer seem acceptable.

Reflecting the emergence of liberal democracy, power did not disappear, indeed it reasserted its presence by shifting its modality. Where a regal power could impress itself upon our physical bodies, power these days depends on two things: a supposedly benign surveillant regime, wherein human beings are measured, codified and classified; and, most importantly, the deployment of that data surreptitiously that creates a tacit sense of what is normal in human society – and hence what can be seen contrariwise as the Other.

Statistically, the bell curve is a perfect graphic representation of how this practice asserts itself: the lower the standard deviation, the more obvious it is as to what is being considered to be normal in a largely unspoken fashion. Meanwhile, the outliers to the left and the right of that mean are Othered by the process, even if that is not the name that is given to it.

While the royal personage was empowered to impress themselves upon us in a physical manner, acting directly on our bodies and allowing others to see what they were in some way entitled to do to us, contemporary power is something that becomes part of us. We incorporate it into ourselves, often without expressly recognising what we have done.

As a human subject, we find ourselves inscribed in myriad bell curves across a wide range of topics. Unknowingly, we are acknowledging normalcy and otherness in each of those…and invariably we incorporate into our presence, practice and thinking the understanding of the world that derives from those statistical representations of humankind.

A pressure can then perhaps be felt to be arising for all of us to be part of the mean rather than one of the outliers. Power shifts to act less ON us..and more THROUGH us.

Compulsory Corporate Fun

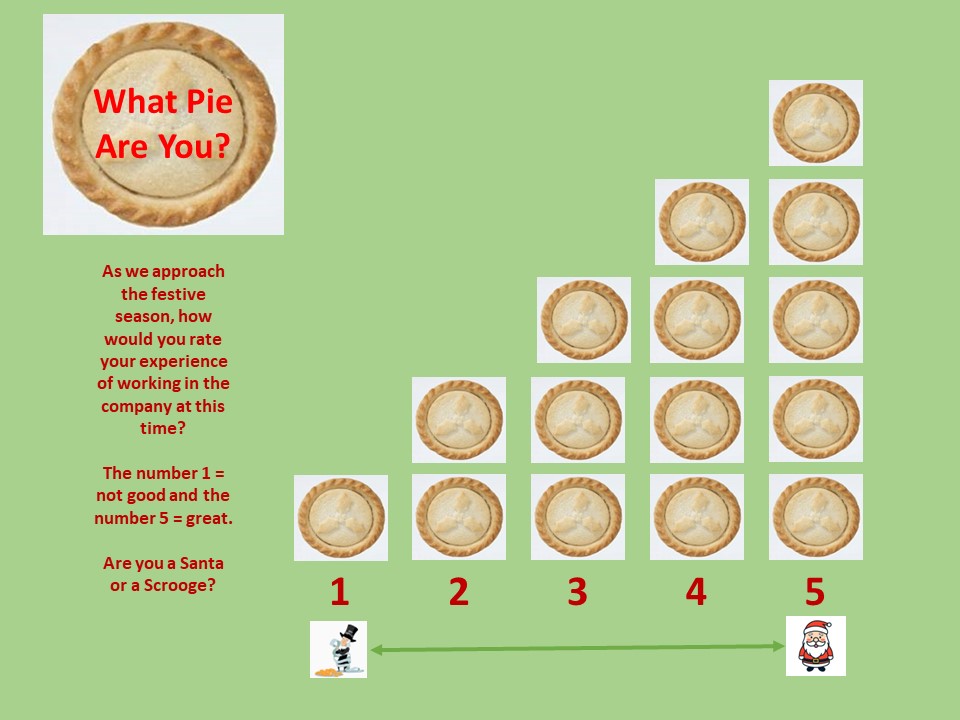

When someone starts to advocate “fun” in the workplace, it often involves playing childish games on an away-day or responding to a frivolous survey like the one I have created here, which draws upon the festive season as its context.

“What’s wrong with that?”, I hear some people ask. “It’s just a bit of fun.” Which, of course, brings us back to where we started. In fact, it is worth considering three key aspects of the use of something like this, with which many of us will be painfully familiar. (I recall at one time being confronted at the start of a meeting with pictures of six pieces of toast of varying shades of brown, into which an approximation of a human face had been carved, from a beaming smile to a sad downturned mouth and eyes. We were all invited to declare which piece of toast best reflected our state of mind. Without doubt, some people eagerly engaged and were amused by it. Others probably took part because of the pressure they felt to be seen to be engaging in the “fun”. And a few, I suspect, rejected the whole exercise, something difficult to do, of course, because to do so would be to end up as the Other.)

First, the “fun” here is an imposition on everybody – and is playing a purpose. It serves to homogenize the workforce – “Every one here likes fun, right? So what’s not to like about this bit of silliness?” – and it achieves this effect through the tyranny of what is assumed to be a majority (although no one’s opinion on this sort of exercise is ever sought). What looks like mere levity can in fact be seen as a cultural stricture that engenders compliance.

Second, through exercises like this, we can lose sight of the important fact that the workforce is made up of grown-ups with specific adult needs that can be partially met by participation in work that is both meaningful and that also offers some autonomy. As a result, some might well find this sort of activity infantilising and belittling, although – in the name of “enforced jollity” – the very idea that someone might not be as enamoured of this as it is assumed the majority are is simply not entertainable.

If we unthinkingly institute activities that inadvertently treat our audience as children, taking an approach that leads us to use exercises more suited to the primary school classroom, we may titillate some of those with whom we work, perhaps even a majority of them. But we will antagonise others, who potentially, through the action of what is called pluralistic ignorance – opting for silence about a specific issue on the unfounded assumption that everyone around you are assuming the opposite position – will be left isolated and irritated. A colleague shared with me an exercise that an OD facilitator had forced on their audience at a “team building away day” and, when I checked, this artifact had been deliberately designed for use with Key Stage 1 children.

Discursively, embracing a childish approach to creating connection and supporting improvement in the workplace has a power effect that may not be our intention, but which needs to be recognised: specifically, if our work either deliberately or inadvertently infantilises the workforce, those people are less likely to be engaged with seriously and in an adult-to-adult fashion. The subtle undertone to any exchange is going to be shaped by casting these people as something other than mature adults.

The Victorian axiom that “Children should be seen and not heard” can be heard to be echoing around in this context – and suddenly corporate leadership seems to be assuming a parental voice. From a transactional analysis perspective, workplace dialogue seems to be taking place between the parent and the child state, as opposed to being an adult to adult exchange that would be the most respectful and conversationally productive.

Lastly, the type of fun showcased in the mock exercise being used as an example here diminishes our existence as human agents, negating the experience of our life in favour of a tick on a Likert scale. It belittles people’s experiences in the workplace by reducing them to a clumsy parlour game, designed merely to entertain.

Through its humorous reduction of the actual living of a life as a human being to an agglomeration of simplified data, it is a reminder that we are all reducible to what Haggerty & Ericson (2000) refer to as our data double. That presence is increasingly the one to which corporate leaders turn in order to make sense of their organisational context, a shadow of ourselves that occupies cyberspace and consists of formal information collected and collated about us.

At work, of course, our data double is built out of all the information that the company accumulates about us: HR data; performance appraisals; talent reviews; grievance and disciplinary paperwork; and compliments and complaints. This version of ourselves is allowed voice in annual staff and pulse surveys…but is the interlocutor of choice for those who occupy senior leadership positions, interrogated in lieu of meaningful adult discussion with the flesh, blood and mind imbued person who turns up in the workplace each day.

What’s below the surface?

Webster was much possessed by death

And saw the skull beneath the skin;

And breastless creatures under ground

Leaned backward with a lipless grin.

Daffodil bulbs instead of balls

Stared from the sockets of the eyes!

He knew that thought clings round dead limbs

Tightening its lusts and luxuries.

T. S. Eliot, Whispers of Immortality

Some who take time to read this might be led to think that I am being far too miserable in the face of what is simply a bit of fun. Eliot’s assessment of Webster’s morbid frame of mind casts him as a gloomy soul, although some might equally say that he was a realist, paying attention to the very thing most of us work so hard to avoid thinking about.

In the spirit of Webster, we need occasionally to look below the surface, to reassure ourselves that there is nothing lurking underneath that might be more sinister than first appearances might suggest. It is also worth noting here that sometimes a hidden purpose has been deliberately created by someone, particularly someone with positional power.

But in most instances things arise organically out of a complex constellation of inter alia modes of thinking about things, overarching views of the world, ideas for how things should be, and ways of getting along in a practical sense. But we are still often impacted and constrained by their appearance, even where no overarching individual or group have created them.

The next time someone offers you something fun to do, just think: Fun for whom? Whose definition of fun? And what might the hidden effect of that fun be on me – and on those who are around me?

And the next time you are asked to create and host a session for people in the workplace and you’re tempted to go down the fun route, quickly ask yourself: This might feel like fun to me, but how might others experience it? And what (or whose) agenda might inadvertently be served by going down the notionally fun route?