Finding ways to think differently about our NHS

At the start of February, the Kings Fund helpfully made space for an article by Deborah Fenney that looked at how anarchist ideas might have currency in the current circumstances faced by health and social care.

Laura usefully acknowledged very early on in the piece how anarchism carries with it a raft of negative connotations. The word tends to conjure up images of 19th Century activists, lobbing primitive bombs into royal carriages in the Balkans.

The vitality of autonomy

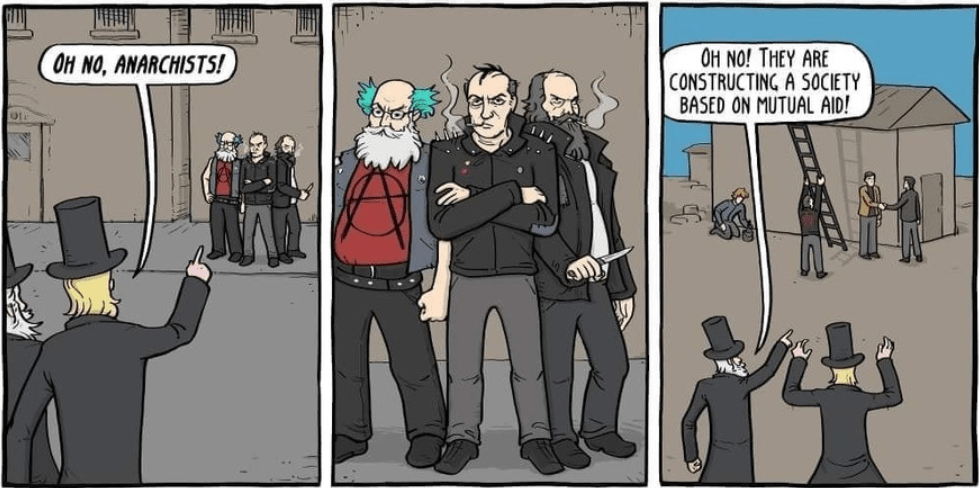

But this is a political tradition that encompasses a range of notions that can be sensitively applied to the situations that we currently face. For example, Rhiannon Firth has written brilliantly about how exceptional crises lead to the appearance of grassroots Mutual Aid, a notion originally mobilised by Kropotkin that sought to refute Darwin’s hierarchical “survival of the fittest”.

So, for example, in discussing this disaster anarchy, Firth identifies how people put traditional constraining structures behind them when something like Hurricane Sandy or Covid-19 strikes and the state seemingly crumples in face of the situation and disappears. Instead, they come together as a collective to get the essential things done without relying on the state.

Rethinking leadership

Importantly, in this context, it is worth remembering that anarchism recognises the fluid nature of leadership yet refutes the notion that particular individuals should assume the abstracted role of leader.

In conversations with clinical staff where they reflected on their practical experience of health care during the Covid-19 pandemic, I heard from my interlocutors how senior leadership seemingly disappeared in the early stages of the crisis, which meant that those staff felt compelled to step into leadership.

In so doing, the silos fell away and the distance between agencies seemed to narrow, as people abandoned structure in favour of exploiting extant and developing networks. As the bureaucratised constraints frayed in face of the need to get things done in the crisis, things sped up and seemed more effective. One example offered was arranging a patient transfer, which went from involving a good many people and taking at least three days to simply requiring one clinician to call another to make things happen in half a day.

Rethinking organisation

One of the fictions that exist in regard to anarchism as a political approach is the idea that it is formless and chaotic. As we have seen in respect to leadership, it simply looks to find different ways of tackling the challenges of human society. It does not reject organisation, it merely seeks to find new ways of organising. Reinforcing this idea is a seminal text in the tradition that talks about the tyranny of structurelessness.

Anarchism is not in pursuit of the popularly accepted idea of anarchy. Instead, it critiques current structures and – lacking the overweening, overbearing and innately oppressive political programmes so beloved of socialists and communists – constantly experiments with new ideas about how society might work in practice.

Anarchist ideas to support our debate

First and foremost, this political tradition attends to the challenge of freedom. Whereas other progressive ideologies fetishize the state as an instrument that can be seized and used to engender socio-economic change, anarchism sees that state as the major problem, something that inhibits our freedom.

This is why anarchists are so concerned with thinking about how society might be differently organised and seek to constantly envisage and test out ways in which that might happen.

A second element of this has latterly appeared in discussions about anarchism, namely the extent to which one’s political practice needs to be prefigurative. In essence, this can be simply expressed as indicating that the ends cannot be argued to justify the means.

Instead, the ends need to constantly inform and direct the means; our practice needs to be consistent with our aim, as an ethical politics isn’t just about the goal. Instead, it needs to be reflected as we make our way towards that goal – and needs to be consistent with it.

This reminds us of one of Myron Rogers exquisite maxims, which are there to encourage us to reframe our thinking about organisations in capitalist society and how we might think positively about change in them: “The process you use to get to the future is the future you get.”

As noted above, while anarchism is constantly exploring new ways of organising, it tends to eschew the idea of having a model or vision that needs to be imposed. In critiquing the work of Marx in respect to the state, the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin in 1873 – a full 44 years before the Russian revolution – suggested that communist theory in relation to the state would lead to ‘the despotism of the ruling minority’.

Any overarching perspective and plan has the tendency to become dogma – and, once it acquires that status, it ends up subsuming and silencing the very people that this vision is meant to be liberating. Whether this a political programme or a corporate transformation project, these precept tends to hold. This is why freedom and autonomy are so crucial to anarchism – and why voice is so central to these politics.

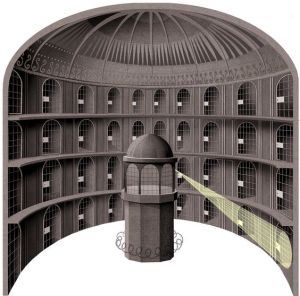

Obviously, anarchism offers a challenge to all forms of power, whether it marches under a conservative banner or a progressive flag. This is why a number of contemporary writers have made a meaningful conceptual connection between traditional anarchist politics and a range of ideas that appear under the rubric of poststructuralist theory. In particular, the link between anarchism’s nuanced understanding of power and the sophisticated analysis of power found in the work of Michel Foucault is often highlighted.

Perhaps the greatest significance of reframing the debate around health and social care in the UK using anarchist ideas is that it actively contests the Labourism that gave birth to the NHS and that continues to shape – perhaps distort is a better word – the service.

This is not to belittle the achievement of the 1945 Labour administration, which remains impressive. It is instead crucial to understand the exact nature of the social democracy that we have in this country, which can be argued to be uniquely statist, in terms of assuming that the state is a neutral instrument that can be used to deliver a political programme.

Statism privileges representative democracy and assumes that change is delivered by government through inhabiting and directing bureaucratised structures. The voice of the wider population goes largely unheard and people’s involvement is negligible, as they are merely seen as beneficiaries of this political beneficence, as opposed to partners in this endeavour. It seems to me that our NHS continues to be tacitly informed by the statism that informed its introduction.

Alongside this obsession with the state as an instrument of change, Labourism can also be seen as both hierarchical and paternalistic. Only a certain cadre of people can occupy the bureaucratised features of the state and pull the levers therein to generate change. Immediately, a two-stage hierarchy emerges. Similarly, that tiny and isolated clique of “change agents” – to use a term in organisation development that is increasingly growing in corporate popularity – occupies a tier above everyone else. And only that group at the pinnacle of the pyramid are deemed to know what is good for the rest of us.

Pulling together the threads

This is not a manifesto, demanding that we seek to build a model of health and social care on the basis of anarchism. Rather, it is an argument to suggest that anarchist ideas might help us all to rethink what is needed to engage with the challenges and realise the ambitions that exist for our NHS at this time.

I have tried to show that these ideas are far from outlandish and dangerous: they offer a refreshed perspective on the circumstances currently faced. They are not solutions in and of themselves, rather they are lenses through which we might view the situation differently. They are not necessarily the right ideas, but there is no doubt that they are different ideas – and eschewing the mental framing; wearisome models and frameworks, and familiar ideas that we have constantly deployed over time with no sense of anything actually changing would seem to make absolute sense.

We can now think about next steps – while, at the same time, rejecting the idea that we need to take giant leaps. Here’s some initial thoughts off the back of this article:

- We could begin by thinking about the NHS in terms of how it is built and what thinking dominates therein.

- We can critically challenge the power arrangements that form its infrastructure.

- We can offer a level of involvement for the population that we seek to serve that is founded on autonomy and genuinely values the voice of those people, a direct involvement as opposed to a managed or representative one.

- We can reflect on how crisis in our systems may have generated significant innovation in terms of what we do and how we do it – and hence look to learn from those experiences.

- And we can expressly recognise that the way we do things is as much part of the process of seeking change as the goals that we ceaselessly set ourselves.

Want to learn more about how fresh thinking might clear a space for working differently? Drop me a line at radicalod@colefellows.co.uk or check out the website at http://www.markcole.org