Just because someone is speaking does not necessarily mean that the person or people with whom they are notionally in conversation are paying attention to what they are saying. It is surely the case that all of us can recollect times where it dawned on us as we shared a story or spoke about how we felt about something that, whilst our interlocutors were acting as though they were paying attention, that was in fact merely an act – and they had not properly heard what it was that we had said.

Say what?

Of course, that idea of an exchange wherein one person speaks and the other listens to the message was theoretically unpicked by the late Stuart Hall back in 1973, when he critiqued this somewhat unidirectional and hierarchic model of speaker and listener by discussing processes of encoding and decoding (pp111-121). This approach suggests that both parties are active in terms of on the one hand crafting a message and on the other interpreting it.

Hall made clear that as two people engage in a communicative exchange, they do not enjoy an unbridled agency in terms of that encoding and decoding; instead, both activities are shaped by a coordinated practice of meaning making – and also by the ideological context in which that exchange takes place.

For example, the way in which I might choose to describe an event that occurred in the workplace will reflect my understanding of what I experienced. It will also be carefully constructed in terms of the people with whom I am seeking to speak – a peer or a senior leader, perhaps – and my specific interpretation of the environment in the moment in which I propose to engage in that speech act.

Similarly, the recipients of the words that I opt to seek to share at that time will, in turn, make sense of them through the prism of their own personal position in the world and will be shaped by the dominant discourse that exists in that organisational setting.

Speaking needs to be heard

October is Speak Up Month in the UK. This offers an opportunity to remind ourselves about all of the challenges of attending meaningfully to voice and silence in social settings. However, there will also no doubt be a flurry of self-congratulatory corporate pronouncements about how well particular people and companies are doing in terms of developing a speak up culture.

While Stuart Hall’s sophisticated reevaluation of communicative exchanges focuses on the quality of that particular interaction, it is worth recalling that the corporate contexts in which so much consideration is given these days to the idea of creating a “speak up” climate are shaped at a deeply structural level by power and hierarchy.

This means that we need to attend both to what is happening at a surface level in an organisation – declarations of openness, apparent commitments to staff involvement and engagement, constant invitations for people to find their voice – while also trying to find out how this is experienced in practice at a much deeper level in this social and dynamic situation.

We need to carefully consider how a corporate setting seemingly creates a context wherein people feel comfortable to speak up, while also checking whether people perceive that culture and act accordingly: “I am invited to speak and it feels safe so to do.” At the same time – and even more importantly – we need to examine whether there is a complimentary context in which everyone, particularly those in senior leadership positions, invest time and effort in a two-fold engagement with the dialogue that they’ve invited: they are actually listening to the voices that they have invited to speak in the workplace – and, even more than that, that they are genuinely hearing and acknowledging what is being said to them and around them, notwithstanding how awkward that message might be for them, in order to move their organisational cultures from speak up to listen up and thence to a genuine and visible commitment to connect-and-converse.

Ways in which people fail to listen

Why is this distinction in terms of workplace culture around voice and silence so important? Because, at work, we do not need to look far to find people seemingly listening but refusing to hear what is being said, insofar as the voices around them are sharing something deeply uncomfortable, which may clearly reflect the negative way in which an organisation is being run.

At senior levels, there is the traditional assumption that such leadership roles are defined by being decisive and directive – both the sole source of ideas and the origin of commands for those to be enacted – rather than connective of people and conversations across a systemic terrain, which is a more insightful contemporary understanding of what leadership needs to be.

It is for this reason that we often find people – particularly those with managerial responsibility – engaging in what are called unlistening practices. One of the these that has particular presence in the workplace is narcissistic listening. This is helpfully described in the following way, which may elicit memories of experiences we have had in the workplace, now and in the past:

Some individuals struggle with listening to others because they prefer to be the center of attention. Narcissistic listening is a form of self-centered and self-absorbed listening in which listeners try to make the interaction about them […]. You might consider this type of listener a “stage-hog.” The narcissistic listener will do one of two things to take over the conversation and bring the focus back to them. They might interrupt and re-route the conversation back to themselves, or they might change the topic completely. Being the center of attention is important to them. They may look away from you as though they are bored, they may frown or pout, or they may ignore you or excuse themselves and leave the conversation. When engaging in a shift response—turning the conversation back to themselves—it might seem that they are trying to outdo you or “one-up” you.

Another practice in this regard is described as pseudo-listening. This is sometimes thought of as a social nicety, wherein – for example – we give the appearance of actively listening to someone who is telling us a story that they have shared with us already on countless occasions. However, when considering a definition of this behaviour, it is apparent that a more pernicious version can often be seen in the workplace: ‘Pseudo-listening is pretending to listen […]. It includes behaving as if you are listening by providing nonverbal or even verbal feedback (back-channel cues) and showing you are paying attention when you are not.’

Far too often in corporate settings – where great stay is placed on the assertion that the organisation actively embraces a speak up culture – there is a depressing amount of pseudo-listening going on, not because the person has heard what is being shared before but because their view of the world simply cannot accommodate what others might be experiencing in that context and seeking to articulate when invited to speak.

Of course people sometimes say something that we would rather not hear. Their perspective may run counter to the one that we hold – and which helps us to feel stable in the world and contain whatever anxiety might be arising for us out of the situation. It is at that time that we need to attend deeply to what has been said and why we have reacted to it in that way.

Similarly, that which they find the opportunity to say may feel like a significant challenge to the status and position in which we have ended up; instead of embracing this and interrogating it reflexively, it is far too often the case that people offer that pretence of listening while actively disregarding what is actually being said. This is perhaps the worst of all worlds: invited to speak; seemingly listened to; actually unheard; and aware that nothing then happens in response to that which we shared.

Embracing hearing and dialogue

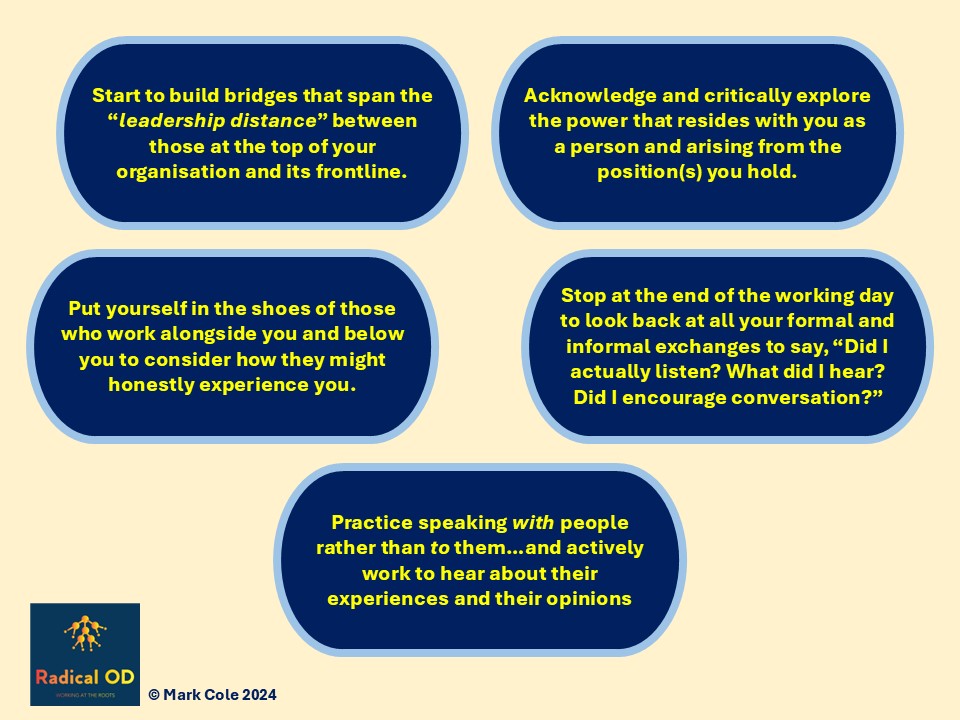

If you want to move your practice away from the theatrical – “I pretend to listen to what you are saying but I’m merely waiting for my cue” – and embrace a way of being and doing that doesn’t just declare that speaking up is important but sees you both turn to yourself to think carefully about your position and how people might react to it and also to actively acknowledge and challenge your own power in a corporate context, you do not have to make this significant leap alone.

Since 2016, John Higgins, Kira Emslie, and I have been doing work with people and in organisations under the rubric of Speak Up, Listen Up (SULU). This draws on the rich research that John has undertaken alongside his colleague Megan Reitz; Kira’s extremely detailed knowledge of the practicalities of voice and being heard; and my years of work around development activity in a range of organisational settings, which found solid expression recently in the book that I co-authored with John, entitled The Great Unheard at Work: Understanding Voice and Silence in Organisations.

Just recently, the three of us have revisited that activity and – through our individual and collective reflexive practice and the fresh understanding that we have developed in light of our work, our research and our writing over time – we are able to offer a significantly refreshed approach to genuinely creating situations that go beyond the superficial and encourage people to speak in light of the fact that those around them have moved beyond performative listening. This document outlines how we are approaching SULU 2.0:

A starting point for stepping into the serious work of thinking about going beyond mere appearances so as to craft and sustain a climate in your workplace where people feel truly safe to speak because they are confident that their voice will be heard, acknowledged and engaged with, is to begin by embracing the following:

From Speak Up Month to a Speak Up, Listen Up life

As noted earlier, October is deemed to be a month where there is a heavy focus on speaking up. But it should also be seen as the stepping off point for an even richer and meaningful commitment to voice in the workplace. In this respect, it is particularly noteworthy this year that the National Guardian’s Office for the National Health Service (NHS) is expressly foregrounding the need to move from simply encouraging people to speak to giving them reason so to do in light of a supportive listening climate in their workplaces.

Hopefully, then, in October 2025, a large number of both public, private and third sector organisations will have started off down the path from speak up to listen up in the workplace…or will be working to further build and enhance the path that they presently have in place. Either way, John, Kira and I are available to advise, guide and support anyone on that journey, so please use the contact details in the SULU document embedded here to invite that assistance, if you feel that it might be of value.