Moving from unthinking defence to engaged development

Early in December, a commentator called Iain Martin contributed an op-ed piece to The Times newspaper that took a critical perspective on the practices of HR management in organisations. The orientation of the article was apparent in terms of the writer’s observation that HR in companies was more fixated on what he described as “wokeness” and not sufficiently attentive to the generation of wealth through effective business practice. Notwithstanding the author’s choice of phrase in this regard, the message was that HR had moved away from its defined purpose of supporting businesses to work effectively.

This followed on from a piece which was published in the New Statesman on 27 November, where a former civil servant called Pamela Dow described her experiences of trying to manage in an organisational context that was significantly shaped by the modern day HR agenda. She pointed out at one point in the article that between 2011 and 2023 the UK has seen an 83% growth of its workforce involved in HR, yet – she argued – there was no correlation in terms of that expansion and an enhancement in terms of productivity.

Managing Conflict

Both these articles observe that historically speaking expanding corporate entities needed to keep records of their growing workforces, which is where we saw Personnel departments emerge. At a time when companies spoke in terms of relations between management and employees (as opposed to indulging in the veiling ideological fiction of leadership and followership) Personnel positioned itself as a useful bridge between those two groups.

In so doing, people working in the field acknowledged the potential presence of different and occasionally contrasting agenda and sought to create a negotiating space. It was also recognised that these agenda could sometimes be so opposed that there was a potential for conflict in the workplace, something that Personnel worked hard to mitigate and often to resolve.

Unfortunately, the discursive shift from recognising the workplace as a site of potential tension to embracing the glib idea that these spaces are now shaped by a notional relationship between leaders and their followers has caused HR to step away from its mediating role. Where once the function was heavily immersed in the business of industrial relations, these days it would seem as though the illusion of followership has effaced this important role.

Additionally, as John Higgins and I argue in our book called Leadership Unravelled, one of the shameful myths that dominate managerialist thinking and practice is the suggestion that “we’re all in this together”. This fiction also undergirds the move from a recognition of the complicated dynamics of human relations in the workplace to one that shrouds this actuality with a distracting corporate gloss – and it has to be stated that it is HR as a function that is in the forefront of creating this illusion.

Current Circumstances in our Organisations

In an ACAS report published in September 2024 that looked at collective workplace conflict, it was noted that two key factors were making it difficult for businesses to acknowledge and work collectively to resolve tensions that arose in the workplace. The authors of this work make the observation that,

Two central themes recurred during data collection and capture the trends identified in this overview of actors, issues, and channels of conflict: The first concerns what we call ‘the knowledge gap’; namely, a general decrease in knowledge about collective conflict, on how to manage it and the role Acas can play in its resolution. The second relates to pressures of the current economic context, which has contributed to polarising the positions of those involved in collective bargaining, making agreements increasingly difficult to reach.

This arises at a time when a feature in the December 2024 edition of Labour Research highlights that there were 3.7mn strike days across the period between June 2022 and April 2023, going on to note that this is the most we have seen since 4.8mn days were recorded between July 1989 and May 1990. In this article, a union national officer is quoted as saying that,

‘What we see now is people graduating as managers/HR officers, who have no experiences of the workplace they are managing and crucially who do not have the relationships with workers/reps that allow for problems to be resolved quickly without the need for a dispute.’

[Labour Research Department (2024) The Changing Face of Disputes. Labour Research. December Edition. p14]

This suggests that the crucial skills set around sustaining and developing industrial relations has diminished over time, as union membership overall has declined and the idea of the workplace as a nexus for disagreement, tension, friction and conflict. Certainly, this deficit was very apparent over recent years as the NHS experienced its biggest and most significant period of industrial unrest for some time.

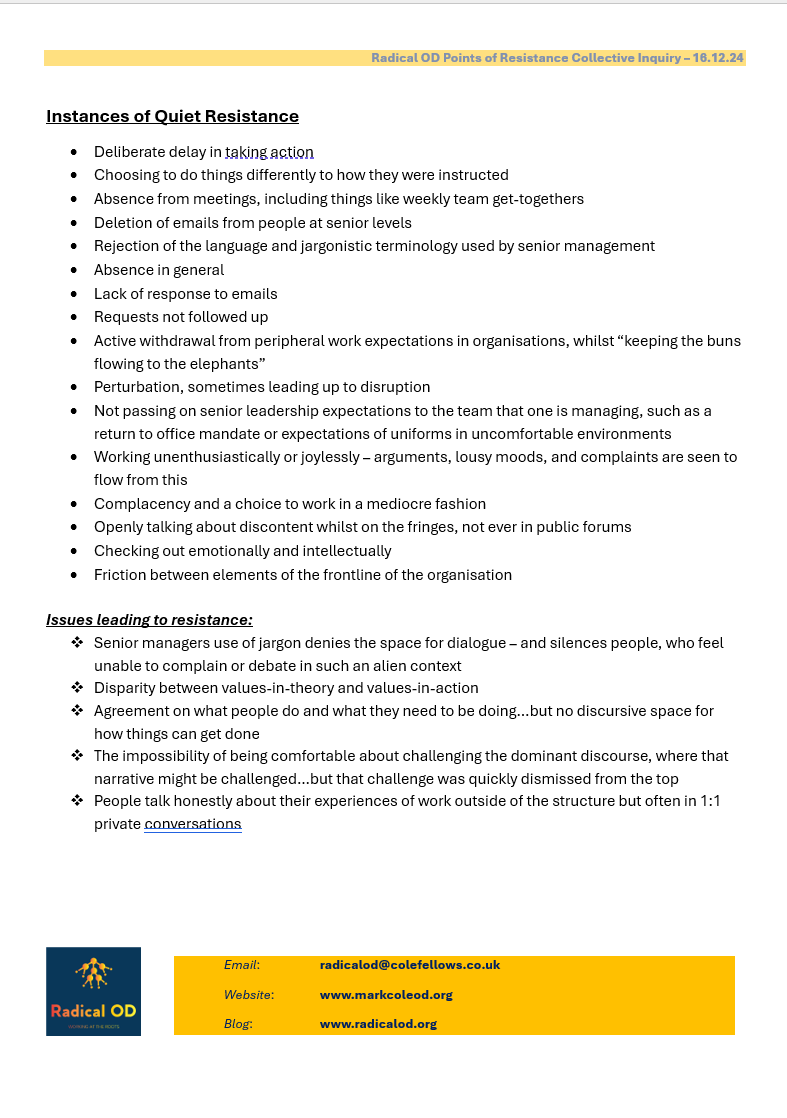

An inquiry that I am currently undertaking is exploring subterranean resistances, those tacit and quiet actions that people take to say no to expectations placed upon them by organisational structures and the management that sits on top of those. These stand in sharp contrast to labour withdrawal and working to rule, activities invariably conducted under the protection of a trade union. Those not in a trade union, sitting in the mythic terrain of leadership-followership, have to find other subtle ways of saying “no”, which often involve the management not actually hearing it. In my inquiry, the following actions are listed by people who responded to the invitation to share their corporate experiences and insights:

All of which reinforces the notion that we have seen a significant shift wherein the HR occupation has abandoned the badge of Personnel and all of the important work that was undertaken under that rubric. Instead, it has embraced the crudely objectifying phrase Human Resources, and has floated free from its grounding in the practicalities of record keeping and providing support to help relations between people at work to be supportive and facilitative.

The Dehumanisation of Human Resources

The appearance of this concept of HR signalled a dehumanising of relations in the workplace, with workers diminished by this deployment of language in a way that suggested a shift in respect to what Martin Buber argues about connections between people, namely a movement where – in some instances – an I-Thou connection existed to one in which the shaping of the conversation signified a shift to the more negative I-It relationship, wherein the subject engages with another as an object rather than as a fellow person.

A Harvard Business Review article that is now approaching ten years old marked socio-economic shifts in the 1970s as a practical pressure that partially led to this shift. It suggests that,

[M]ore and more tasks that had traditionally

been performed by HR (from hiring to development to

compensation decisions) were pushed onto line managers, on top

of their other work. And that’s been the case ever since. HR is now

in the position of trying to get those beleaguered managers to

follow procedures and practices without having any direct power

over them. This is euphemistically called “managing with

ambiguous authority,” but to those on the receiving end, it feels

like nagging and meddling.

This powerful description of how HR has transformed itself from an administrative to an oversight and policing function is a powerful reminder why – as has been my experience of an early life in the workplace where I was a very active shop steward and over a subsequent long career working in and around such departments – there is now a pronounced tension between them and the managers with whom they are expected to work. The rebranding and repositioning of HR has led to a schism wherein I regularly heard HR people complain about managers failing in their responsibilities to actively manage their people – and those managers complaining that HR seemingly failed to involve itself in any of the practical aspects of managing the workforce.

An additional concern in regard to the development from Personnel to HR is that the latter signifies a drastic move away from the role of seeking to affect balance between the workers and the management. Instead, HR is wholly concerned now with acting exclusively as the main channel for the managerial imperative across the entire business and positioning itself as a business function. This is prompted by the critique of HR and its failure to contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of the organisations in which it sits.

For example, one researcher and writer on the topic comments that, ‘For decades, HR has been criticized for being bureaucratic, dysfunctional, and out-of-touch with the reality of what businesses need to do in order to be successful.’ Instead of crafting a distinctive position in corporate life for itself where its approach and expertise could truly add value, HR has merely made itself into the management megaphone, thereby completely losing the trust of the workforce.

The opposite of professional is not amateur

Part of the problem for those of us working in the general field of HR has been the relatively recent focus on professionalisation, an agenda driven by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD). Invariably, this process – embraced by any number of occupations in the contemporary capitalist context that are seeking to justify and rationalise themselves – mirrors the approach of the historic professions, such as medicine, law and the clergy. (This has long been an interest of mine, not least because I matriculated to the University of York to do my first degree on the basis of an hour long interview on campus with the late Professor Andrew Dunsire, discussing how society defines a profession!)

This type of professionalisation is rarely about lifting the quality of what gets done under the specific rubric; instead, it is merely about assertion in the market. It controls entry into an area of practice by seeking to seize control of it. This sees activity such as defining a body of applied knowledge and agreeing how and where it might be practised; setting competences off the back of this generation of boundaries; and, crucially, defining precisely who can and cannot practice in that field. Hence, London black cab drivers are better able to declare themselves to be a profession, as – to ply one’s trade in this way – one needs to complete the Knowledge and obtain a licence on the basis of that undertaking. That workforce and who gets to access it is controlled by a professional body.

An occupation that seeks to professionalise itself should – at the same time as seeking to corner some part of the labour market – also be asking itself fundamental questions about what it presently does and what the occupation would prefer to do in the role that it is defining for itself. Importantly, it should seek independence for itself – another crucial element of the very term “profession” – and act on a basis that eschews standardised and unquestioned perspectives to offer a more sophisticated and nuanced view of matters of concern to the group. Back in 1963 (and with apologies for the sexist appellations used herein) Everett C Hughes argued that,

‘Professions profess. They profess to know better than others the nature of certain matters and to know better than their clients what ails them or their affairs. This is the essence of the professional idea and the professional claim…The professional is expected to think objectively and inquiringly about matters which may be, for laymen, subject to orthodoxy and sentiment which limit intellectual exploration. Further, a person, in his professional may be expected and required to think objectively about matters which he himself would find painful to approach in that way when they affected him personally…A professional has a license to deviate from lay conduct in action and in very mode of thought with respect to the matter that he professes. Since the professional does profess he asks that he be trusted.’

I would suggest that this is a very long way from people’s contemporary experience of HR in their workplace. And perhaps a good many practitioners in the space will aspire to this mode of practice…but will find themselves oppressively limited by the fact that HR is subordinate to the managerialist agenda, and no longer acts independently between the bosses and the employees.

Offensive Defensiveness

This is especially apparent when we consider the response to Iain Martin’s critique of HR that Peter Cheese, the CEO of the CIPD, broadcast via LinkedIn on 7 December. He persisted with the fiction that HR functions these days are still oriented like Personnel Departments by arguing for, ‘HR’s dual responsibility to align with business objectives while being a voice for the workforce presents unique challenges.’ The entire piece was occupationally defensive (in a way that chimed with the institutional defensiveness that is so often central to HR practice in response to managerialist expectations) and did not once pause to ask the question of this field of work, “Is there anything in the critique offered that we should explore in order to improve our practice?”

Reponses to this unthinkingly reactive statement from amongst many working in the field were broadly supportive. People did not focus on how they might be experienced by those affected by their corporate presence and activity in support of the managerial imperative. Instead, there was a strong theme amongst all of the correspondents that there should be a concentration on promoting an occupationally defined understanding of HR, with a focus on the difficulties faced by those engaged in the field; the way in which the practice was now seen to be central to the business of business (as opposed to a generous focus on the workforce); and the expectation that, if HR is promoted solely on the basis of what it thinks it does as opposed to people’s day to day experience of the activity and the people involved, then its profile will be raised and its status enhanced.

All of which suggests either a lack of insight and appreciation for how this work is perceived by people – or, instead, a tacit recognition that this domain of practice has seriously lost its way…coupled with a refusal to challenge what has become the status quo. Thus far, I have offered a critique of HR and what it has allowed itself to become in pursuit of status in the so-called C-Suite. Now, as a Fellow of the CIPD, I’m going to conclude by offering some suggestions as to how we might – as people working in HR – engage our criticality, reflexivity and ethical selves in order to think about what it is we do – and whether we are presently doing it right.

HRD? No, DHR…Developing Human Resources in terms of outlook and activity

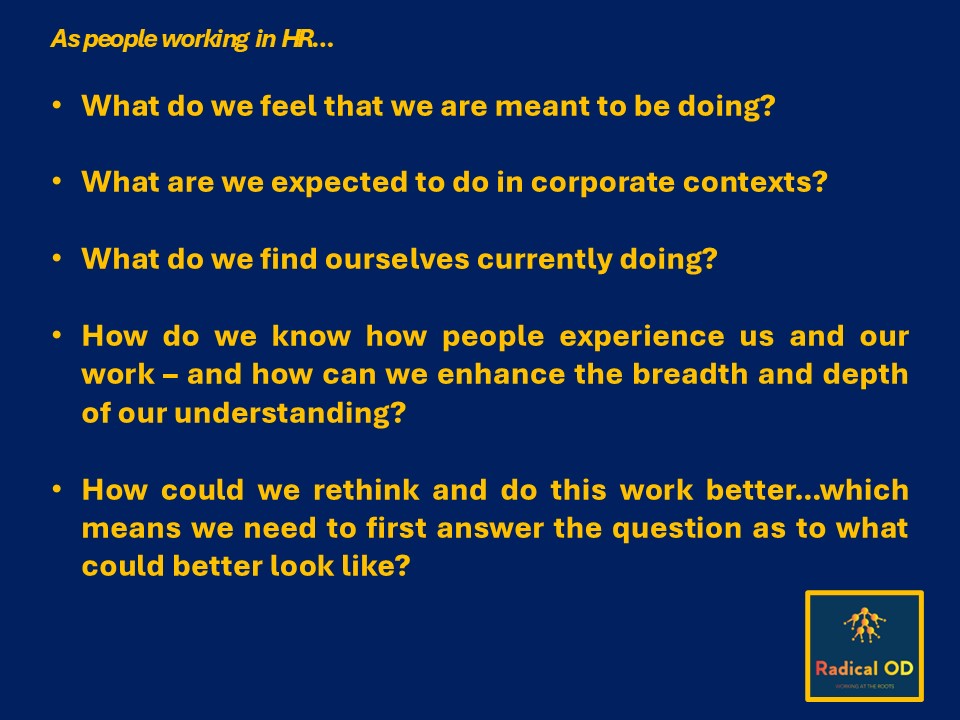

When I first saw Iain Martin’s article, I immediately saw some truths buried underneath the polemic. Some of his observations resonated very strongly with me, not least in light of the fact that – in my book entitled Radical Organisation Development – I had both written a critique of my own organisation development practice across 40 years in the workplace and also drafted a statement alongside that personal critique as to how I intended to orient my work going forward. In response to Martin’s observations, I drafted a cluster of reflective questions that would help people to move beyond reactionary responses to a situation where Martin’s article would offer a positive opportunity to think individually and collectively about what HR means in our contemporary context – and whether that understanding of what the practice does in our organisations is the right one for us, as practitioners and as a collective occupation.

Those questions are as follows:

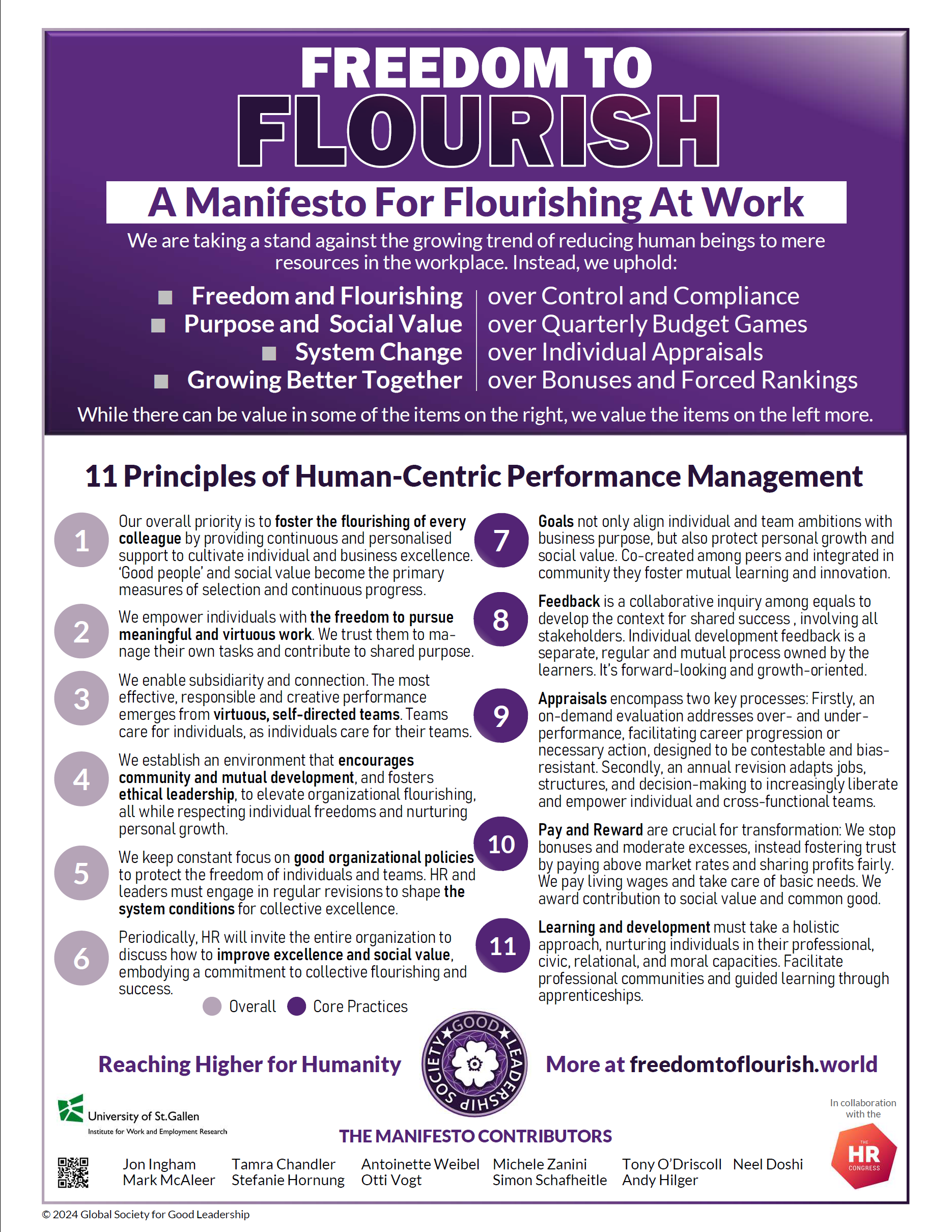

If you want to join me in an inquiry as to how HR can liberate itself from the constraints of contemporary business practice and wearisome expectations of managerialism, in order to truly embrace the idea of being an occupation with a central focus on people, I would be delighted to hear from you. It is worth bearing in mind that some have already started out on a path that focuses exclusively on the human in Human Relations, so there is a already a way in which we can view our world of work differently – and consider ways to embrace a work practice that aims to create work spaces in which people can flourish. Here is their initial manifesto, which offers an excellent starting point once one has asked oneself the difficult questions about what you do, how you do it…and crucially for whom and for what overall purpose.

There is something about the fixity of a manifesto that can often leave me feeling uncomfortable. There is a rigidity about it – and its precepts can oftentimes be seen to define in- and out-groups. However, in this instance, I see the content here as pushing the boundaries of our thinking – and hence offering a useful starting point for individual reflection and collective inquiry. Perhaps even more importantly, the document encompasses six principles, which stands in contrast with the standard corporate fascination with vacuous values that have no realistic impact other than as a managerial tool of compliance and compulsion. To discuss undergirding principles – particularly in a realm of practice that declares that it is a profession – is an essential starting point for meaningful debate around the purpose and potential of the activity that occurs underneath that umbrella.

Other resources are available to coax us out of our protective shells in order that we might make an honest assessment of the work in which we are involved and how our presence and activity is experienced by all those around us in the corporate context. For example, a recent article in the MIT Sloan Management Review provided what the author Ashley Goodall described as A Radical Rethink of HR. Envisaging a Venn diagram which approximates to Harold Bridger’s distinction between a business’ Primary Task – how it delivers the goods and services that mean that it survives in the market – and the Double Task, which is all about the dynamics between people that allow for that delivery to take place effectively and efficiently, the author describes the two circles thus: the first is entirely focused on the needs of the company, while the second is concerned with the interests of the people working there.

This notion importantly brings to the fore in discussions about our organisations the simple – but largely denied at this time – fact that, whilst there is an overlap between these two spheres, they are separate and different. Recognising this – and acknowledging the fact that contemporary HR is way too concerned with the business circle at the expense of the people circle creates space for a deep and rich discussion about that positioning and what HR offers to workplace. Goodall’s analysis of current circumstances and proposal for how things should be is as follows:

Right now, HR sees itself as the implementation arm of the people-related things in the first circle — and this certainly appears to be the role that most businesses want it to play. In many organizations today, HR functions either as an agent of management or as a slightly awkward mediator between employees and management, trying to explain what’s going on to employees while nudging management in a better direction…[Instead] HR’s fundamental accountability must be for all the things in the second circle. HR should become a full-throated advocate for employees and their interests. It should be an expert in understanding the employee experience on the front lines (not just as relayed via senior management) quantitatively and qualitatively, and it should be an expert in what humans need in order to do their best work and to make their fullest contribution. Given that the long-term interests of any organization and the long-term success of its people are one and the same, an enlightened leadership team will ask HR to play this role, and will empower it to do so.

Instead of slipping into a foolish protectiveness when confronted with serious critique of what we do and how we do it, we should instead be seizing the opportunity to think in detail about what we are asked to do, how we end up doing it, and whether there is a better contribution that we could make.

Rather than taking a defensive stance, we should consider the principles that might offer a solid and ethical foundation to the work we do – and, instead of fixating on and fetishizing the arid and vague corporate values that prevail in most business settings, we should ask ourselves the existential question “What are the personal values that bring me to work…and to work in the workplace where I currently reside? And – alongside these – what are the personal values that drive me to do the work that I do…and to do it to the very best of my ability?”