Back in November, I enjoyed a long weekend late in the month at my favourite place in North Norfolk. We combined this with a trip to the Thursford Christmas Spectacular, a magnificent festive show that runs every year.

Over the course of the four days that we were there, I got my usual newspapers from the shop on site…and also picked up copies of the excellent Eastern Daily Press and the East Anglian Daily Times.

These two newspapers are important reminders of why regional publications and their journalism are crucial social resources, because they were both actively and openly holding to account local companies and organisations that exercise considerable corporate power. In particular, they were at the time of my visit effectively challenging the statist and undemocratic practices of local NHS organisations.

The two stories on which they were focused at that time strike me as offering important insight into the challenges faced by people working in health and social care at this time – and the urgent need for them to abandon past practice in order to embrace a more open approach and creative approach.

1. Holding the Systems to Account

On 22 November 2024, the EDP continued to report on a story where Norfolk County Council as part of the Integrated Care System in the area had decided to close a facility in the town of Cromer that offered a service for people fit for hospital discharge but still requiring some care before going home.

It had been run by the NHS until 2017, then transferred to NCC until the decision was made to close the provision in 2023. The BBC reported in September 2024 that ‘In a recent survey of nearly 300 people, the watchdog Healthwatch found 79% wanted it to be used again for convalescence. But the Norfolk and Waveney Integrated Care Board (ICB) said it could not find a way to make that work and would “return the site to NHS Property Services”.’

Statism as an obstacle to creativity

Here, writ large, is the failure of the NHS to ever seriously address the democratic deficit that has existed since its inception in 1948. As taxpayers and service-users, we are invited to say what the managerialists that lead the service want us to say…but we are denied any means to actively be in ongoing discussion with the administration of health care services.

Previously, there was a significant difference in this regard between the monolithic structures of the NHS – born of the erroneous Labourist obsession with statism, the idea that the state is a neutral structure that can be used to establish and manage publicly funded provision – and the democratic foundations of local authorities, providing accountability through the electoral relationship that exists between local populations and their representatives.

It would now appear that the introduction of ICBs – which can presently be clearly seen as statist structures that are dominated by the NHS – has seen the absorption of local authority functions in respect to care and the consequent erosion of that accountability. In a style that sustains the aloofness of the NHS culture and its approach to engagement, the ICB in question – under the stewardship of controversial Labourite dame Patricia Hewitt – took the unilateral decision to close Benjamin Court and then – having delivered a fait accompli – invited the local Healthwatch to consult with local people on how the buildings on that site might now be used.

Just 295 took time to respond to this invitation, quite probably because they knew that they were being asked to be a chorus of support for a decision already made and impossible to change. Nevertheless, 79% replied to say that they wanted the service to be reopened; as ever, health care bureaucrats made a pretence of listening but refused to hear what was actually being said.

A new kind of health service management?

Ideologically, the emergence of Integrated Care Systems was meant to presage a change in direction for health and social care towards a focus on population health and a commitment to deliver a service that is actively designed to support local needs. A progressive ICB would be looking to find new ways of properly hearing and acknowledging the voices of local people, in a style that seeks to sustain an ongoing conversation, as opposed to a secular catechism.

Such a move would require leadership courage in contrast to bureaucratic compliance. But when we talk about the vitality of speaking up, this refers as much to those buttoning their lips in the boardroom as it does to people immersed in the business of the business.

2. The Persistence of New Public Management

Meanwhile, further south in the region, the East Anglian Daily Press reported on 25 November 2024 that the East Suffolk and North Essex NHS Foundation Trust (ESNEFT) had decided to extend the outsourcing of support services such as portering, cleaning, and housekeeping across the organisation.

One of their hospitals had this provision provided privately under a contract that was drawing to an end: the Trust was now proposing to extend outsourcing in these areas of activity to every site in the organisation. In light of this, the Unison branch at ESNEFT was launching a series of strike days.

The withdrawal of labour is a costly act…for the strikers

One of the first things I learned on the Certificate in Industrial Relations and Trade Union Studies course at Middlesex Polytechnic I undertook back in the mid-80s was that strikes were not things that staff easily embraced. They were the action of last resort, when dialogue had withered away, and crucially strikes hit the pockets of those withdrawing their labour…who, in this instance, are very likely to be amongst the most poorly paid of a workforce coming together to offer the best possible health care service to the populations across that region.

Just to compound matters, the report in the paper indicated that the ‘ESNEFT board was due to make a decision at a public meeting earlier this month but will now meet in secret on December 5 to make its final decision on awarding a soft facilities contract.’

I have no doubt that the board would seek to justify this lack of accountability to their staff and the populations that they are charged to support as necessary in light of the fact that it is a commercial discussion, but it serves as a reminder of how distanced these corporations are from those of us that they are established to serve – and who provide the tax-pounds that allow them to function.

The Values Gap writ large

As management and a group of employees who deliver crucial services alongside the clinical staff at the very frontline of the business go head-to-head on this issue, a cursory glance at the corporate values serves a reminder of just how meaningless these can be.

In so many organisations, there is a leadership distance, where the senior management find themselves far away – and isolated from – the practicalities of what it is that the business does, which leads them to look outwards instead of inwards and focus on abstract elements of organisational life – such as visions, missions, and values – that have little real impact on the lives lived in the corporate setting; similarly, one can far too often find a values distance, where values-in-theory and values-in-practice sit way too far apart.

ESNEFT has taken a CBeebies approach to conjuring up its values by making sure that they produce the acronym OAK. These stand for Optimistic, Appreciative, and Kind…which raises the inevitable question as to whether the values or the abbreviation came first. In the familiar Orwellian style of these simplistic exercises, the Trust outlines what this means as follows:

‘For everyone this means: Optimistic – We will work together positively to make time matter for all our patients and staff; Appreciative – We understand and value the role we all have in delivering better patient care every day; Kind – We will value diversity and provide a caring and listening environment for all our patients and staff.’

Immediately, in light of the collapse of industrial relations in the organisation, I feel compelled to ask the following questions:

- To what extent are the roles of those about to find themselves transferred from NHS employment into the private sector being valued, particularly in respect to the question of whether in-house or outsourced services of this sort are seen be to better or worse in terms of patient experience?

- How much does the workforce feel as though they are working in an organisational environment in which they are cared for as human beings – as opposed to abstract entries in the accounts – and actively listened to?

In practice, the values that seem to be dominating these circumstances are those of New Public Management, the corporate manifestation of neo-liberalism that arose out of Thatcherism and flourished under Blair’s New Labour administrations. In essence, this looks to import thinking and activity from the private and into the public sector…and, in particular, represents the apotheosis of managerialism with a decidedly Taylorist feel to it.

Stop reproducing the past and allow the future to emerge

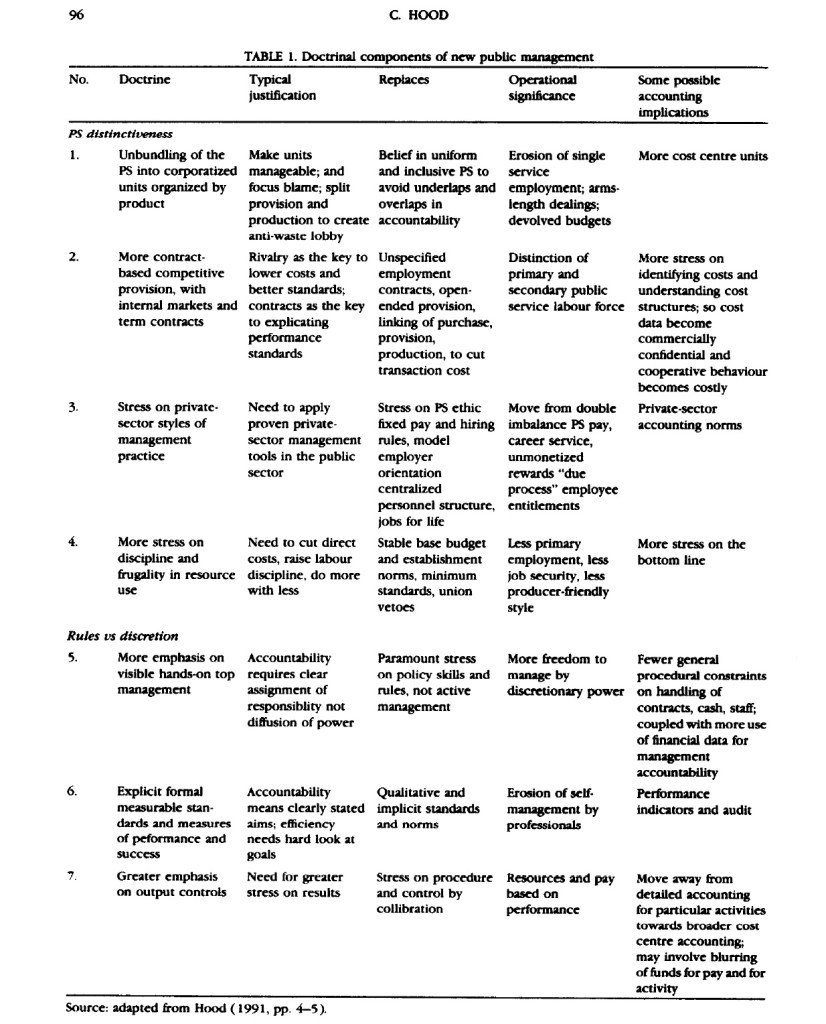

A leading writer in the field – Christopher Hood – observes (1991) that the arrival of NPM appears to derive from four larger socio-economic trends, one of which is ‘the shift toward privatization and quasi-privatization and away from core government institutions, with renewed emphasis on “subsidiarity” in service provision.’ In an article four years later, Hood conveniently outlined what he took to be the key seven foundations of NPM, which are summarised in that 1995 paper in the following table:

Ultimately, the current Labour government – despite much discussion about reducing the number of targets in the NHS, with the Financial Times this month reporting a numerical drop from 32 to 16 targets – is still drawn to NPM, which puts great stay on seeking to manage activity by demanding that it achieve targets, which leads to a distorted focus on the prioritised indicators and a resultant failure to attend to all the others…along with a tendency for those being measured to seek to game the system.

It looked before the election as though Wes Streeting would bring an innovative and adventurous perspective to trying to rethink health and social care. Thus far, however, the practice is all sounding very 1997, as if he has been drastically absorbed by the structure and is now at a distance to the service, the people who work there, and those that depend upon this provision.

What could be done?

I have argued elsewhere that what health and social care needs at this time – in particular, in the NHS (which organisationally and culturally tends to dominate Integrated Care Systems) – is not another ineffective reorganisation but instead space and time to develop genuine dialogue with staff and citizens (often one and the same person, in terms of the populations that reside around large hospital Trusts) and find ways out of those conversations to rationalise the way in which things are done.

After 77 years of reactive managerialism, the NHS has ossified. The absence of space for dialogue across the service has transformed from an accident that arose out of the way in which the NHS was put together back in 1948 to a governing principle of the leadership of the service. This despite the public statements constantly inviting people to speak up that occur in the service, requests that have signally failed to generate a speak-up culture, quite the contrary in fact.

My experience of reading about local issues for our NHS back in November 2024 merely underscores for me how the service is constantly a focus of change – and yet it tends to remain exactly as it has always been. It is unaccountable, unengaged with the people that matter, and uncomfortable with ideas that might fundamentally – and for the better – shake it to its foundations.

This is why I am of the opinion that the major challenge for the NHS at this time is supporting leaders to open themselves up to the fundamental issues of voice, silence and power in the organisations that make it up…and to start to experiment with ways not just to listen to what people are saying but truly hear what it is they are discussing – and taking that as a lead, in terms of what needs to be done.

This is precisely the work that I do, in terms of both my scholarship and my organisational practice. There is enormous potential in the development of Integrated Care Systems…but that can only be realised through active and open-minded exploration of how to address the challenges and embrace the ambitions in health and social care. Such a dialogue potentially creates the space for new ways of doing things and new ways of managing things to emerge, which is the point at which progress can start to be made.