This government’s stuttering approach over NHS England over recent weeks has apparently culminated in a decision to close the organisation.

The NHS has felt somewhat managerially top heavy for a while now. With the arrival of the 42 Integrated Care Systems, we were confronted with three managerial structures seeking to support health services to meet their challenges and achieve their ambitions. In light of the ICSs appearing beside both DHSC and NHSE, it felt as though some consideration was required.

The Drawbacks of “Decisiveness”

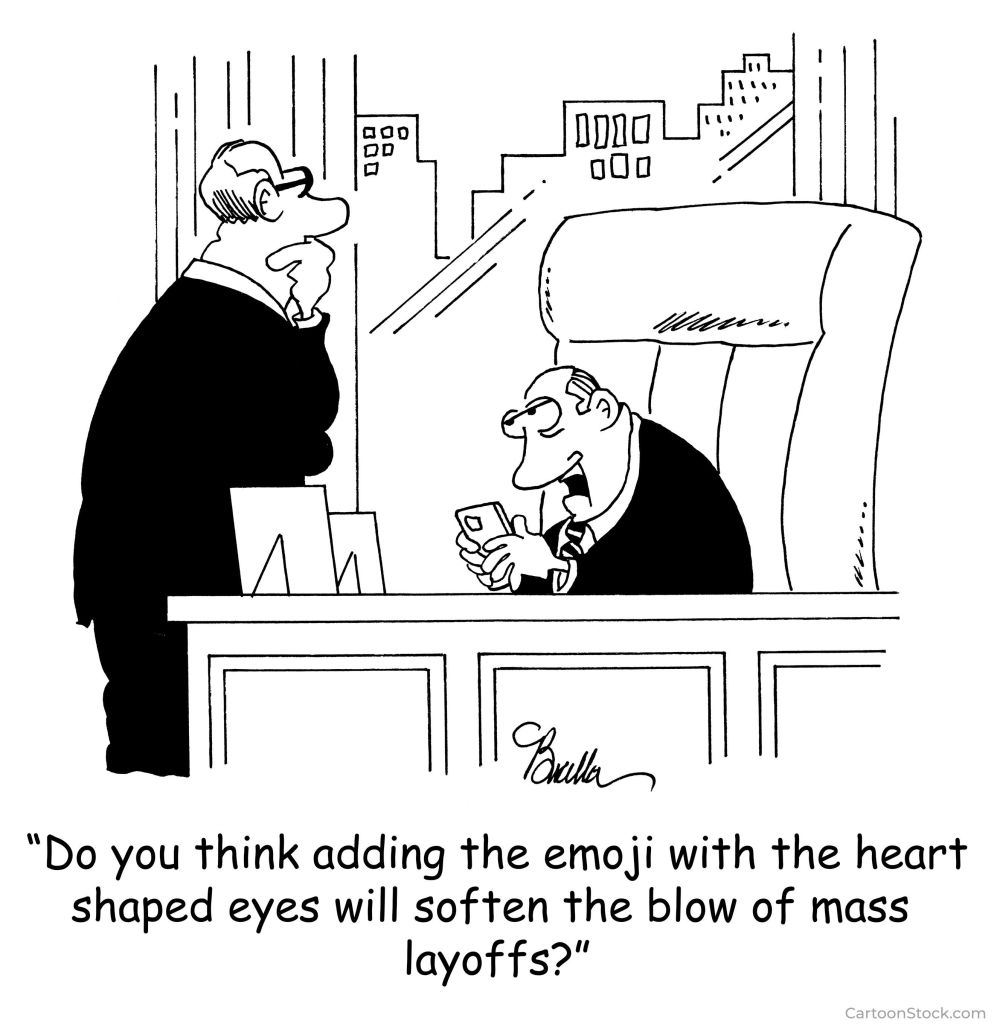

Regardless of whether we feel that editing NHSE out of the picture is the right or wrong decision, the way in which the Labour government have led this process raises a number of issues. In many ways it mirrors the poor practice that we so often see in the wider corporate world.

First, there is the way in which the final announcement about abolition was made, which meant that the staff affected heard about it via media reports of the Prime Minister’s speech that contained this commitment. At best this is clumsy and unthinking, at worst actually cruel.

Second, there has been a strong sense surrounding this affair of a focus on what Megan Reitz and John Higgins in their excellent research and analysis into spaciousness in the workplace call the doing mode.

Instead of seeing the political leadership taking a gentle and expansive stroll around the issues and reaching an unplanned yet suitable destination, we have watched them canter through woodland at full pelt to arrive at a place that was seemingly always where they were headed.

Third, there is much talk of the removal of 10,000 jobs, which seems to be undergirded by the idea that this will be a message well received by the population at large – and especially the electorate.

Yet it is not simply 10,000 jobs being vanished from the ledger; it is 10,000 stories of lives lived to date, current expectations and ambitions, and immediate requirements and needs. It is potentially 10,000 plans immediately put on hold – and 10,000 lives put on pause.

When Humanity Goes Missing in Management

Each individual in that dehumanising aggregation will have in most instances been doing what was expected from them in the organisation. That expectation – and the purpose and meaning that is, to a greater or lesser extent, derived from our paid employment – has seemingly disappeared in an instant.

The term “redundancy” will be used to speak of settlements and the like but it will not address the deep-seated feeling of being redundant, of no longer being of use. I was surprised about how this sensation consumed me two years ago, when I accepted voluntary redundancy from NHSE. I am concerned as to how this effect might impact those who are implicated in these changes.

Without doubt, the powers that be will shortly be busily throwing support at all of those affected. There will probably be much talk of resilience and provision of outplacement services. Ultimately, though, some of that impact that needs now to be offset could have been avoided had the government thought more about the effect of the announcement rather than the optics.

Bringing Important Issues to the Fore

In all of the discussion about this across social media, I was particularly impressed by two contributions. First, there was an important analysis of the importance of management in the NHS from Mike Chitty. It is a reminder that the demise of NHS England should not cause us to denigrate the practice of management in a corporation the size of the NHS that operates in complicated and complex circumstances.

I regularly cite the 1973 article by Jo Freeman that grew out of anarchist politics and the women’s movement, entitled The Tyranny of Structurelessness. It states that – where people come together in a shared endeavour – meaningful and clear shape and direction are always needed.

But this is far from the exclusive preserve of those at the top of hierarchical structures who assume the title of leader. Indeed, the adherence to positional power by those people denies the fact that leadership is a space into which a range of individuals might step, depending on the specific circumstance faced and the capacity that they bring to the situation.

Alongside Mike’s thoughtful contribution, there was a helpful piece by Claire Price-Dowd on how the range of arm’s length bodies associated with the NHS have contributed to the effectiveness and development of our health service.

Far too often in the course of organisational change, the contribution made to date is shunted into the sidings under the descriptive title of “legacy”. It renders this an historical artefact rather than a resource that does not merely evaporate when someone chooses to “transform” or dismantle a corporate space.

Interestingly, Claire mentions what the short-lived NHS University (NHSU) offered to the service. I worked in this organisation across the duration of its two-year existence. One of the key initiatives that it was my job to promote was a staff induction package that was designed to onboard people into the NHS as a significant and cohesive national corporate entity. It was designed to complement the local induction into the specific organisation that they were joining.

No sooner had NHSU been closed down, all of its resources disappeared. And, just the other week, as an indication of the circularity of so much developmental work in and around the NHS – I saw an announcement that NHS England was about to launch a national induction programme.

In terms of my experience of the decision to close that organisation, I recall the hastily called all-staff meeting at 88 Wood Street, the NHSU HQ. I can still envisage the wave of incredulity that washed across the room as the most senior person there announced that we were instantly being shown the door…but, in the spirit of David Brent, then declaring that it wasn’t all bad news as the work would continue, because they had been appointed to a national role at the Department of Health.

All of which was deeply disconcerting and upsetting. But, in my heart I knew that NHSU had run its course and that – given the amount of tax-pounds invested in it – the return on investment overall had not been good. Ethically, I sensed that this closure – despite the fact that it filled me with dread in terms of needing a salary and worrying about not having a job – was in some way personally beneficial, as it released me from those circumstances.

In my early thirties, I had spent eight months on the dole…and I found it soul-destroying and deeply depressing, so I have always lived in fear of joblessness, something reinforced by my working-class background which emphasised that you should always be in work and earning a wage, regardless of what it was you ended up doing. So being pushed out of the door at NHSU had a huge impact on me.

Where are we now, and what might be next?

In November last year, I penned an article that sought to review where the NHS was in light of the impact of the pandemic, alongside the challenges that it faced and the ambitions that existed for it. I concluded at the time that the managerial centre of the corporation was simply too busy, particularly with the arrival of 42 Integrated Care Systems.

It was clear to me that there was little point in yet another reorganisation: these interventions in the NHS since its inception in 1948 made a lot of noise about change but merely created disruption and failed to alter things meaningfully.

However, in light of the presence of the ICS tier; the expanded role for the Department of Health and the danger of duplication across the various bodies; and the provenance of NHS England and the changed circumstances in which it now sat, I felt that there was room for a rationalisation of the functions covered by those three structures.

There is virtue in a carefully considered and spacious conversation about what management at the centre of the NHS should look like – and what its relationship should be with the business of the business, in respect to provider organisations. But that’s not what we’re currently seeing…and the impact of what is happening will be felt negatively by the people implicated.

It is deeply worrying that the proposed abolition of NHSE is taking place alongside a drastic downsizing of the ICSs. This is a particularly concerning development, insofar as these structures are that much closer to the practicalities of service delivery – and really need the space and time to engage in meaningful dialogue and to think creatively about how to support the service to meet its challenges and achieve its ambitions.

And – in terms of the bottom line in all of this – it is vital that those people driving these changes forward step away from a purely technocrat perspective and remind themselves of the 10,000 individuals that are implicated and set to be affected.

Those leaders have made a mess of the messaging thus far; they need to step back, pause, and begin to practise a form of leadership that is fully in contact with their humanity and the feelings of those implicated.