The modalities of power that serve to stifle our voices

The application of physical power by figures in authority is often seen as something consigned to the annals of history. Michel Foucault’s analysis describes a shift from sovereign power – the capacity for a figure literally lording it over us to apply actual punishment to us in order to force our compliance – to disciplinary power, in response to our societies experiencing major changes in terms of industrialisation, urbanisation, and democratisation.

Hence, our redefinition in this instance as citizens instead of subjects demanded a change in the way in which power was thought about and experienced. A key element was the expansion of surveillance, wherein the dramatically extending state – and the burgeoning professions such as psychology – began to watch us all very carefully, something of which we were constantly aware and by which we were directly affected.

By watching, I mean that these agencies began to gather data about us. Being aware that this data collection is taking place serves to compel us all to internalise the idea that we are potentially being watched at all times – although, on many occasions, no one is actually attending to what we are saying and doing. And this assumption that someone is watching means that we tend to adjust our behaviour to ensure that we are compliant if they were to turn their attention to us.

Similarly, disciplinary power – as well as being surveillant – arises out of the concatenation of power itself and knowledge. As the state mobilises its huge volume of statistical data, the notion of normalcy emerges: if you analyse a population in regard to some variable, the bell curve defines what is deemed to be normal…and, in so doing, identifies – at either side of that parabola – the outliers, who find themselves Othered by this approach.

The Experience of Sovereign Power

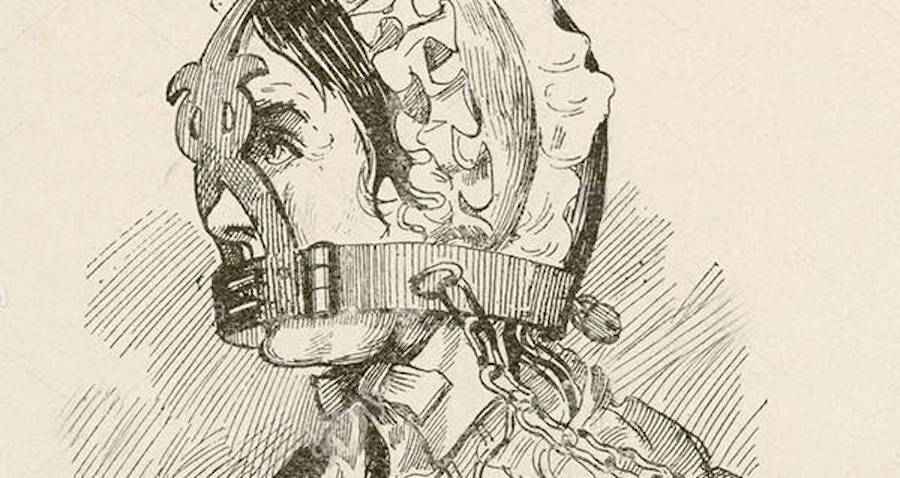

Sovereign power acted upon the human body in all manner of grim methods. And the misogyny involved in terms of who most needed silencing in that social context is extremely apparent in respect to the grotesque device called the scold’s bridle.

As these pictures horrifically demonstrate, this mechanism was applied pretty much exclusively to women – and included a metal plate that went into the mouth to flatten the tongue. These plates often had a spike underneath them in order to prevent the tongue from moving altogether. Hence, the wearer would be unable to say anything without injuring themselves.

There were also instances of tongues being physically removed, particularly where the object of this procedure was deemed to have blasphemed. A specialist pair of tongs were designed to facilitate this operation: they were used to torment people with, in terms of torturing them by stretching and twisting their tongues…and they were also used to stretch out the tongue from an open mouth in order to cut it out of the person.

This saw sovereign power acting upon this bodily part in two ways. Firstly, by using pain to try and compel people to speak. And, secondly, by taking the opportunity to prevent the person from ever speaking out again.

Moving between modes of power

It is reassuring to be able to ascribe these ghastly behaviours to a distant past. While things are undoubtedly better now, in most instances, power continues to undergird our relationships – and now finds more nuanced and less physical ways of shutting us up. But it is still present and continues to constrain us.

One crucial shift in this regard is the move from power acting upon us in a physical sense to power being absorbed by us and shaping from within how we are in the world and what we do there. Whereas in the past, the person taking a contrary position to the dominant discourse might have had their tongue ripped out, these days people “hold their tongues” and silence themselves for fear of the social media pile-on or of being cancelled.

Whilst it can often look as though we are being constantly invited to openly express our views, the climate in corporate settings tends to remind us that taking a contrary position is still seen as heresy. What can and can’t be said is tacitly present in all of our exchanges at work.

There are things that we are encouraged to say at work; there are things we feel comfortable saying; and there are things that we will withhold in the workplace. A range of practices, policies and procedures – both structural and cultural – conspire to control our speech. This is where the power has shifted from the application of tongs and a sharp knife to the active promotion through a range of channels of a dominant discourse.

No one is having their tongue ripped away or being paraded around with a vicious frame around their head these days. This is because power has developed new ways to exert itself in response to wider social shifts. But power is still with us, in terms of stifling our voices and subtly demanding silence in a wide range of settings.

Reflexively engaging in your changed circumstance

As you go about your working life in this changed domain, pause a moment to reflect on how free you feel to use your voice as you would want to and to say what is in your mind…and consider what contemporary practices exist in corporate life that offer a less brutal way of managing what you say and rendering you silent on some occasions than a scold’s bridle or tongue tongs.

The liveried representatives of that power wait beside an apparatus which has as it sole purpose the decapitation of its victims. Being executed by the guillotine is the ultimate act of silencing.

In the foreground of the picture, of course, there is an avuncular priest offering the last rites to the person about to be beheaded. Despite belief in an afterlife, it is apparent that their soul will no longer have an existence in this realm…and this cruel act precedes transit into a realm of silence, as the living do not get to see heaven so voices therein cannot be heard.

For those who find themselves working behind the label of manager or leader in these corporate contexts, you need to appreciate that, whilst you no longer enjoy the authority to act physically on those below you in the hierarchy, you will still be affecting them in terms of constraining their voices or demanding their silence through your presence and practice in that role.

For example, prioritising your understanding of circumstances that are being faced serves to position your view as the dominant one. Notwithstanding whether you have a personal commitment to hearing the voices of those around you, it remains the case that this dominance subtly limits the space for other voices, particularly those in subaltern positions.

Asserting that your perspective is the one that should enjoy a privileged position in an organisational context – not because it is seen to be an accurate interpretation but because it arises out of where you find yourself in the structure – is a long way from using tongue tongs or affixing a scold’s bridle to someone. However, that said, the method is drastically altered but power remains unchanged beneath the surface of a practice deemed to be more liberal.

Power is consistently present; it is merely its modality that has shifted.