LinkedIn offers a rich insight into the fads and trends that come and go in the world of business. Watching these fashions wax and wane is a constant and depressing reminder that the world of work can be seen to lack depth and seriousness.

Instead, it is awash with models, frameworks and checklists. In that regard, a statistician called George E. P. Box has the following quote attributed to him, which is constantly cited in order to justify the lack of creative and critical thinking that goes on in business: ‘All models are wrong, but some are useful.’

Professional Camouflage

There was a time when I avidly collected resources related to organisation development (OD). As soon as I spotted some new diagram that notionally would help me to do my work, I downloaded it and stored it in a computer folder.

This space stretched and stretched to accommodate all that I added to it…and yet I now realise that I never accessed and used anything in there. Which, of course, meant that I never assessed any artefact in respect to its validity and applicability.

Having recently immersed myself in existentialist thought in respect to a new book that I have written that explores how we live our working lives and how we could mindfully be living it differently, I now recognise that I was professionally acting in bad faith.

By this I mean that I was distracting myself from the practicalities of being a person thoughtfully doing my work by immersing myself in material that – through its accumulation – intimated that I was doing my work in the way that those around me were doing theirs.

Hiding Behind Titles

I was also very focused on the names of the roles that I was asked to undertake in corporate settings. This wasn’t just about attracting kudos in response to a named position that had seniority or status attached to it. Instead, I wanted titles for my workplace roles that indicated that I was part of a professionalised community of people doing complicated, specialist and positive work.

This focus, of course, can hardly be thought to be surprising in situations which, by and large are always hierarchical. In keeping with French and Raven’s analysis of a range of modalities of workplace power, for most of my career I could not be said to possess coercive or reward power, both of which tend to derive from position in an organisational structure. However, I was patently seeking to hollow out a position for myself wherein I was in possession of what those authors refer to as expert power.

I have been compelled to reflect back on all of this in light of the fact that it has lately appeared to me that more and more people working in my broadly defined field of practice were cropping up on my LinkedIn feed and referring to themselves as Change Managers, Change Champions, or something similar.

These sorts of titles served to put a distracting gloss on the actual work that we end up doing in such roles. They hide the fact that such activity is about operationalising managerial imperatives in which the workforce at large has ordinarily played no meaningful part in defining and ideologically imposing change on people in their corporate contexts.

In a capitalist society, we all of us have to earn a living – but we need in these circumstances to be honest with ourselves and those who are impacted by what we are asked to do. This self-candour and openness with those affected by us would be a positive political act of minor resistance in the world of work, standing in sharp contrast with a silenced compliance with the ways of being therein.

This, for me, would be about working occupationally in good faith. It entails me stepping away from the definitions that exist in the workplace for what I do and how I am expected to do it. Instead, I feel motivated to immerse myself in my professional existence…and to embrace my own personal way of doing the work that I do. Instead of defining myself by attaching a specific job title to myself, I will instead define what I do by actively taking responsibility for doing it in the moment.

If we don’t engage critically with everything in the world of work – including the jobs that we do, the things that we are expected to do in those roles, and the impact of our activities on others – we are reproducing the structures and cultures that currently exist instead of seeking out better ways of coming together to get things done alongside other people.

What lies behind “Facilitation”?

After Change Managers came a LinkedIn focus on both a range of activities which fell under the rubric of facilitation and also on people who described themselves as facilitators. Certainly, this is how I have referred to myself in a good many instances throughout my career – lately I have once again engaged with that experience critically, reflexively and ethically to see what lies behind these terms.

Two things quickly came to light for me in terms of this personal inquiry. Firstly, in light of where I find myself now regarding the vital importance of voice and silence in the workplace, I realised that facilitation had involved me crafting a structure for each event that I was asked to run, a framework that was notionally flexible but to which I tended to stick, insofar as I was charged with the responsibility of running the event – even though the event could quite comfortably run itself.

Crucially, the existence of a tightly timetabled schedule for the day controlled the voices in the space that I was facilitating. It denied the possibility for expansive and unexpected conversation amongst the adults involved in the event. It compels the group to focus on the topics that the facilitator brings to the room – and the way in which the facilitator has chosen for the group to engage with it.

Importantly, though, whilst the facilitator enjoys some relative autonomy in the space that they are expected to craft and control, it remains the case that, by and large, we are dancing to a managerial tune…and creating programmes that are exclusively focused on the managerial agenda – in terms of the focus and expectations of outcome.

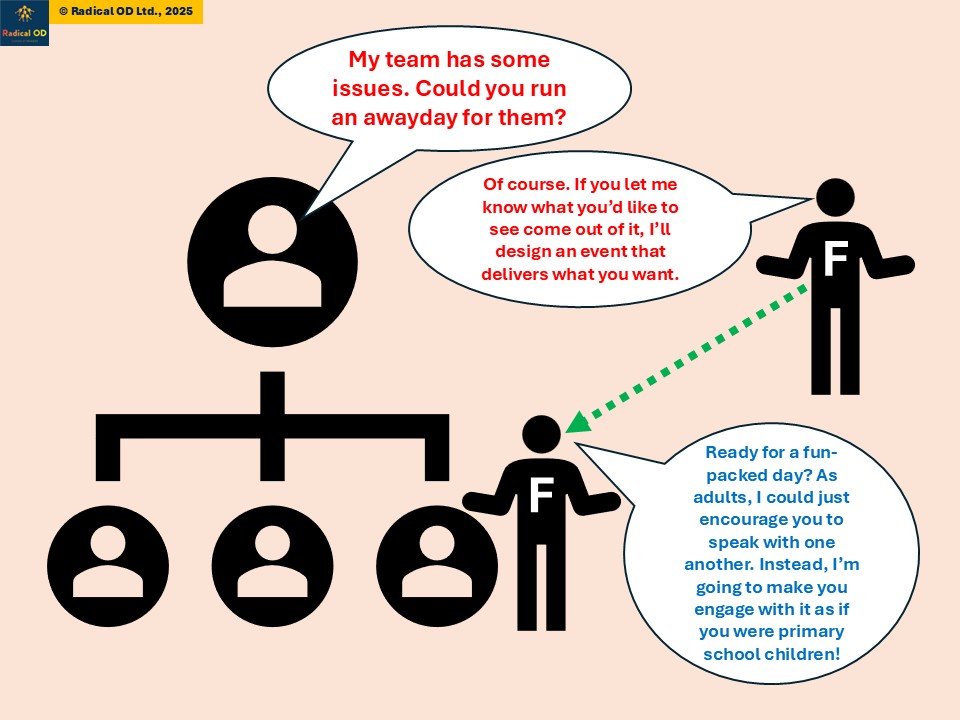

I can think of many occasions where someone in a senior managerial position instructed me to craft an event for the staff with whom they worked. I am conscious now that I merely absorbed the agenda that they were advancing and operationalised it in the event that I then designed and delivered. In an act of bad faith, I opted to refuse to acknowledge the fact that I felt uncomfortable behaving in this way and thereby acting as an apparently unreflective instrument of managerialism.

Secondly, I am ashamed to concede that one of the reasons that I was able to derive so much personal – as opposed to professional – pleasure from facilitation was that I fed off the positive feedback of the groups with whom I worked. I would leaven my sessions with humour and bask in the laughter of the people with whom I was working. But I see this now as meaning that I was too much focused on being a light entertainer, as opposed to the host of an adult-to-adult conversation. As I think about this now, I can’t help but see so much facilitation in corporate life as a grim collision between business and show business…

There is also a theme emerging in respect to this domain of practice that states how wearing and difficult it is to act as a facilitator in the world of work. Certainly, the minute before starting to work with a group has always been dominated for me by an intense sense of nervousness. I recognise now at a deeply personal level that this arose partly out of the fact that, in terms of assuming the role of facilitator, I was placing huge pressure on myself to both engage those in the room whilst, at the same time, meeting the expectations of those who had commissioned me to undertake this piece of work.

Similarly, because of the light entertainment focus of so much facilitation work, I was also concerned to hold the interest of the people with whom I was working throughout the session that I had designed for them. Again, this is an anxiety that arises from embracing facilitation in the way in which it is currently considered in a business setting.

Finally, it seems apparent that if I opt to assume the role of facilitator – and undertake facilitation as a heavily structured process with a clear sense of expectation in terms of what should come out of it – I am merely acting as a managerial instrument. The term facilitator suggests that I am engaged in something exotic and different to normal corporate practice: instead, it is merely a different way for managers to assume the ends they need – and I have become complicit in that.

The Business of Being an Intermediary

I was always acutely aware of the fact that, when I was asked to facilitate something, such as a team meeting or an awayday, the senior manager who commissioned me to do this work invariably absented themselves from it. I was asked to work with their workforce…but they did not seem to see themselves as part of that group.

On reflection now, I am extremely mindful that they were effectively outsourcing a key element of their role to someone called a facilitator. Instead of seeing themselves as an integral part of that work group, they were distancing themselves from it. Instead of creating a climate around themselves wherein everyone would feel comfortable to engage in ongoing and candid dialogue, they opted instead to retain the services of someone to design and manage a specific event, wherein the participants would jump through hoops designed by the facilitator in light of the requirements of the manager to achieve an end already defined.

The icebreaker is deemed to be a way in which people familiarise themselves with one another or relax into the idea of talking with one another in a structured session. But it also serves to erode resistance to what is happening in the space dedicated to the awayday. (This term is important ideologically as well: it indicates an important discussion about work taking place a considerable way away from it!)

For many people involved in such instances, the icebreaker is something that fills them with dread. It can often encompass intrusive expectations, such as the request that people share with the group something that is not known by those with whom they work. In this regard, there is a manipulative assumption on the part of facilitative practice that compelling people to share intimate details will in some way lead to a more “honest” exchange. Yet there is a dishonesty at the heart of an event like this, in that so much is taking place below its surface.

Thereafter, the facilitated session spirals off into requirements that people undertake exercises or discussions, all of which are carefully designed by the facilitator. You might be asked to build the tallest tower you can using sticks of dry spaghetti and some marshmallows: even worse that that, you might invited/instructed to play with a packet of Danish toy building bricks!

I am somewhat ashamed when I look back on my years of practice in facilitation that a lot of the things that I have invited people to do in programmes that I put together may well have left them feeling infantilised. This is why – as I reflected more and more critically on the work of OD – I ended up openly discussing with colleagues and peers as to whether the work that facilitators ended up doing wasn’t actually about connection and conversation. Instead, it seemed to offer people a brief vacation away from the daily grind of the workplace, a moment of distracting entertainment, a fleeting moment of respite.

Promoting Dialogue in the Workplace

If, as I am suggesting, businesses rely on facilitators to release the senior leaders from having to lead the discussions, this means that we are missing a chance to make a genuine difference in terms of voice and silence in the workplace.

A reliance on facilitation in corporate settings suggests a profound dialogic gap between the management and the employees, which is so often the case. Instead of coming together as a group in order to explore common purpose through an active adult conversation, leaders commission an event from which they tend to absent themselves and which imposes a heavy structure and series of expectations on those who do take part . Someone “neutral” needs to be present in order to create an artificial environment wherein the mere approximation of candid conversation can occur. And, very often, the facilitator is substituting for the manager, pursuing the managerial imperative as opposed to truly seeking an honest and sustainable conversation at work.

As we all of us know, saying “No” to requests in the workplace is far from easy in a context where we depend on the cash that flows from the roles into which we allow ourselves to be corralled. But if we are serious about abandoning what is currently meant by facilitation – the conversion of the corporate agenda into a day or two of light entertainment – and actively embracing our potential as convenors of people who come together in dialogue, embracing everyone in the work group, then we need to find small ways in which to begin to resist.

A starting point for this is to redefine the way in which we think about what we do. That means actively abandoning the model of how we should be that derives from the management of the place where we work. Instead, we should actively be crafting our own presence and practice as someone who wishes to enable people to find their voice and use it to share all that they are content to speak about with all of the others around them.

Over the past few years, I have tried to adhere to the following three principles:

- I will actively think of myself as a catalyst as opposed to an intermediary.

- I will aim to act as a mere host rather than a compere, holding space and time for others to use rather than seeking to fill it with distractions for those involved.

- I will look to be a conversationalist instead of a light entertainer, aiming to engage dialogically with people as opposed to delivering a scripted or improvised amusing monologue for those with whom I am asked to work.

Ultimately, it is the responsibility of all of us involved in work that can be largely described as facilitation to stop thinking about our personal needs and instead focus on the professional needs of those with whom we find ourselves working. Ultimately, of course, this will involve us finding our voices and speaking up on behalf of the need for dialogue in the workplace – and thereby actively contesting what underlies facilitative working at this time, which is a failure of managers to take the lead on supporting conversation amongst those with whom they work.