It’s not just what you do – but how you do it

The rationalisation of the complicated field of health and social care is being actively pursued by the Secretary of State, Wes Streeting. As many have noted, absorbing NHS England into the Department of Health and Social care is an impactful choice of action, particularly in respect to the many people working in these spaces who are endeavouring to do the best they can within the organisational bounds in which they find themselves.

It is unacceptable to view the effect upon the workforce as mere collateral damage. Attention should have been closely paid (and needs now to be closely paid) to the way in which the process is being discussed and managed…and how best to mitigate the adverse experiences of the individuals implicated. As ever in so-called change processes like this one, people involved will be confronted by the phony notions of consultation (rest assured, you are invited to share your views but only the most superficial elements will be incorporated into the changes, so the overall project will – in all honesty – remain largely unaltered) and the provision of active support for those implicated, which will probably end up being a series of somewhat wearisome and condescending resilience workshops.

All of this is compounded by the fact that downsizing processes are now also in train across the Integrated Care Systems (ICS). The reductions here will add to the pool of people being shown the door in the NHS, which in turn leaves people affected by the NHSE/DHSC merger with a diminished range of potential opportunities to which they might turn in response to their redundancy. Unless these linked projects end up as exercises wherein Streeting might simply be seen to be rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic, the implications in terms of joblessness are significant.

The Need for Change

However, there is a clear rationale for some sort of rationalisation to take place in the NHS. We should not lose sight of this imperative because of the adverse reactions of those implicated in this shift. It is not a question as to if these things should happen; rather, it is a matter of how they should be undertaken, in terms of protecting those affected.

Specifically, the service has ended up being occupied by three bureaucracies, in respect to NHSE, the DHSC, and the various ICS. Insofar as NHSE arose out of the Lansley reforms, which are now well and truly condemned to the dustbin of history (and politically should never have been introduced in the first place), it makes sense to find ways to focus on the interrogation of the work that needs to be undertaken at a more strategic level, in contrast to that which is delivered by the rich tapestry of NHS provider organisations, and to thereby create streamlined structures to undertake that more precisely defined and sensibly reduced activity.

Given the emphasis that exists in respect to trying to encourage health and social care to think and work more systemically, the current assault on the network of ICSs seems particularly benighted. They have their own shortcomings, of course, but are locally configured and have potential as agencies to work differently and connect with others in order so to do. Reducing their presence leads to the sense that we may be witnessing a somewhat typical Labourite centralisation and over reliance on the national state. (Unlike its social democratic counterparts in Europe, the Labour Party here never meaningfully incorporated Marxism into its ideology. Crucially, this means that it tends to view the state as a neutral instrument to be actively occupied and used, as opposed to a class-based structure that needs to be challenged.)

Rationalisation or Unthinking Reduction?

We are now confronted by the news that Streeting’s rationalisation has extended to the dismantling of a number of organisations that have a focus on health and social care – and yet sit on its corporate periphery so that they can enjoy some semblance of independence. These arms length bodies or quasi-autonomous non-governmental agencies (ALBs or QUANGOs) include two agencies that have a focus on attending to the voices of both the people who work in the NHS and the populations to which it provides its services, namely the National Guardian’s Office and the range of Healthwatch organisations.

The former has always been of particular interest to me, in light of my professional and personal focus on voice, silence and power in the workplace. As with the way in which those employed in NHSE and DHSC have been unthinkingly treated, the announcement of the closure of these initiatives has been made in a crudely technocratic manner – another feature of Labourite politics – with little or no recognition of the issues that strongly justified the creation of these organisations.

It is simply not enough to pronounce an intention to abolish such entities under the crude slogan that more doers and less checkers are required in the system. The Secretary of State should have made expressly clear his intention to ensure that there will be a continued – and potentially expanded – policy and practice emphasis across health and social care to ensure that people are confident to use their voices – and reassured that what they share will actually be heard.

Crucially, it is worth reflecting on: how these organisations now condemned to closure arrived in the environment; the thinking that has undergirded how they have sought to meet the requirements of their respective missions; and the extent to which they have been unhelpfully shaped by the managerialist and bureaucratised context in which they arose. For example, the principle that staff and patients should be able to speak up and be properly heard is crucial, so there is a need for us to carefully consider the experience that surrounds these organisations. If, as Streeting asserts, Healthwatch is guilty of ventriloquism, how has that become the case, in terms of the context and environment in which it sought to achieve its ambition?

An initial observation in advance of a serious inquiry around these issues is that it is possible to interpret the overall approach to supporting the freedom to speak up as one that failed to strike at the heart of the issue – the fact that the NHS has for 77 years sustained both an oppressive and hierarchised structure, alongside a managerial culture founded upon silencing – and instead lapsed into a metrics driven activity based on caseload.

For instance, at one point in my NHS career, I raised a personal experience of having had legitimate concerns around an ongoing change process actively silenced by the organisation in which I worked with four different freedom to speak up (FTSU) guardians therein, including both the Executive Director and the NED with responsibility in this area.

Aside from a single and decidedly glib “thank you for your email” reply, I received no meaningful response from the latter two – and the other guardians with whom I spoke were caught in a bureaucratised process that appeared to simply require them to log the issue and then latterly to tick it off as resolved. Again, I am not denigrating the efforts of those individuals, who took on this responsibility on top of their full time jobs and – unlike trade union representatives – were not entitled to any form of facility time. Instead, I am using this instance as a reminder that corporate environments tend to corporatize everything set up inside or alongside them.

So, at one level, it is profoundly disappointing to see the National Guardian’s Office going, as it can be interpreted as a failure at the centre to take the very idea of speaking up seriously. But it’s disappearance may actually and helpfully open up the possibility that people in the NHS can be encouraged to take the topic seriously…and to approach it in a systemic, systematic and radical way, so that real organisational change arises out of a climate wherein what people actually say truly matters, rather than just logging the numbers of people saying things.

Managing Change Kindly…and Changing Management Approach

The ideological dominance of managerialism in the NHS occupies the space in which serious and deep-rooted cultural work might take place in respect to genuinely attending to the voices of both staff and those to whom service is meant to be provided. In the former regard, the managerialist privileging of metricisation sees human experience reduced to crudely aggregated figures in the NHS’s annual staff survey. That corporate concentration solely on the figures means that the actual experiences that people working in the service endure are dominated, effaced and hence denied by the focus on those numbers.

Similarly, the FTSU initiative across the NHS has raised the profile of speaking up but has ended up concentrating exclusively on numericised cases – and has thence missed the opportunity to challenge the overall culture – and local management climates – of the NHS. The power dynamics that facilitate leadership across the service to pay lip service to speaking up but to refuse to hear what people are actually saying about what’s going on for them in their workplaces are left untouched by the fact that the issue of speaking up has been bureaucratically absorbed by the dominant discourse of corporate life in the health service.

So, let’s avoid becoming obsessed with the disappearance of an organisation and focus instead on the reason that it first came into existence, with the intention that we look anew at this topic with the clear intent of doing more radical and systemic work in this area.

It’s about returning to first principles, whilst – at the same time – engaging reflexively with the practicalities that emerged out of this perceived need. In the case of the National Guardian’s Office, that would involve inquiring again in depth and with a high degree of candour into the issues of voice and silence in health and social care. (It’s one thing to assert that the corporate context wants to hear the voices of all those who work therein…but the reality is far too often that what is then said is either disregarded or actively denigrated by precisely those who should be paying attention.)

Thereafter, it would involve careful and critical analysis of what emerged out of this stated need – and the extent to which the response addressed it. Here, an exploration involving appreciative inquiry would be beneficial: what positive impact did this initiative create…and, at the same time, how was it sidelined from its focus by the structural and cultural context in which it sought to operate.

Such investigation highlights how people and organisations are profoundly impacted by the environments in which they find themselves – and the need to constantly cycle back to reconnect with the key issues on which the response is founded. In calling out the effects of the situations that we experience, we are able to bring the central issue to the foreground again and again – and to explore how the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that prevail in the workplace constrain our responses and serve to endlessly reproduce the extant situation, instead of creating space for meaningful and organic change.

Secondly, let’s remind ourselves that – whether you are a Secretary of State or a Director of an NHS trust – visiting structural change upon people is likely to have quite profound and potentially painfully disruptive effects upon those implicated. This means that we need to discard the cruel and depersonalising notion of Human Resources – and, instead of just replacing that phrase with the word “People”, we should genuinely put people at the centre not just of our thinking and practice…but of our human existence and presence in the world.

The Gap between Map and Territory

It’s now the case that 168 pages of political boilerplate has appeared under the hubristic notion of offering a 10-year plan for the NHS. An exercise referred to as a consultation occurred in advance of this document being pulled together…but this was done at arm’s length, with people invited to respond to a set of questions. Hence, this activity was a long way from authentic and constant dialogue and more akin to a catechism.

In fact, it’s more like a theatrical performance: staff and citizens (which reminds us that the staff are citizens and potential users of the local services wherein they work) are urged to appear momentarily on the stage to deliver lines in response to the cues that they receive. Once they’ve completed the scene, the performance comes to an end and no further engagement occurs until the next scripted and fleeting exchange is staged.

The Covid pandemic offered a major challenge to the assumed certainties of managerialism by making patently clear that – despite the ideologised view of how business is amenable to oversight and active direction – human existence is uncertain and unknowable. This is particularly the case in organisational settings, where the notions that certain of us are equipped to manage and lead in this context tend to prevail.

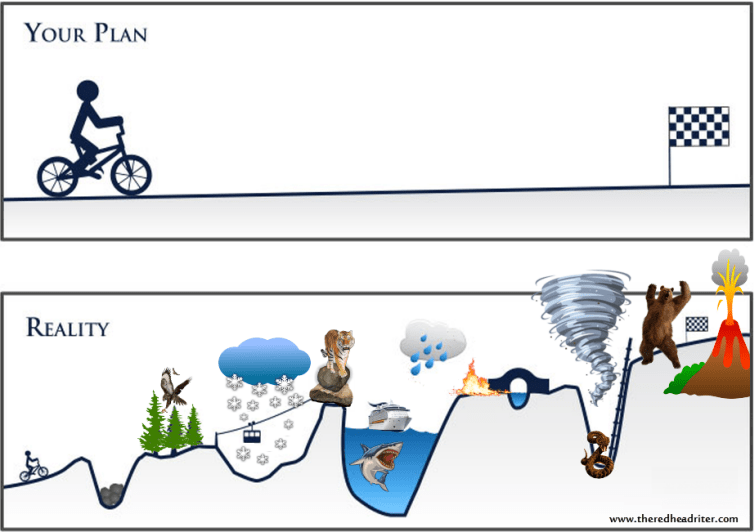

If we accept this analysis of what it means to be human and how corporate practice erroneously suggests that life is in some way directly manageable, then we are forced to confront the government’s new document in respect to health and social care as an absurd fiction. One cannot sensibly plan for a 10 year period without embracing an approach that challenges the linearity that underpins it. For example, if we succumb to the scientism of “If I do Action A, then Outcome Z will automatically result”, we will assume that there is an inevitability in respect to what might arise from our efforts to offer a guide as to what needs to be done – and how it should be undertaken. In philosophy, this is referred to as voluntarism: if I will it, it will happen.

Hence, we need to take take to task the idea that it is in some way possible to meaningfully create a plan across the period of a decade. The reality is that we might forecast events across that span of time but we simply cannot be sure in any honest fashion as to what is likely to occur the day after the plan publicly appears or the day before the end of its 10 year period.

The very term “plan” is problematic because it asserts a false fixity of such documents. Instead, we need to acknowledge that such work is considerably more fluid – and needs to discard the idea of defined destination and a series of fixed milestones to meet it. Attending to feedback loops in respect to any piece of work like this that seeks to describe an overall intention and to outline specific ideas as to how that might be met is the way in which we can engage more flexibly with an ever-changing world. This is where systems thinking can usefully challenge traditional ways in which things have been thought about and done in corporate settings.

Enduring the Same Old Same Old

Looking at the Executive Summary of the NHS plan that recently appeared, it quickly became apparent as far as I was concerned that, while superficially it was looking to the future in terms of the next decade, in fact it was actually looking backward over the preceding 77 years since the post-war Labour administration started operationalised a Liberal plan for crafting an all-encompassing welfare state. Here are six themes that leapt out at me as I sat in a coffee shop in Hertford and – whilst supping my flat white – paid careful attention to the summary and allowed the text to deconstruct under my readership.

Technophilia

Of course it is important to scrutinise and capitalise on all of the technological developments that exist that might improve people’s health and their access to care. But it is equally vital not to fetishize technology at the expense of more human aspects of what it means to provide a comprehensive service in a new way that is efficient, effective and experienced positively.

The excitedness in the document about apps and AI ignores that fact that it is the interface between human agents and technology that generates benefit rather than the kit itself. Too strong a focus on the latter pushes people into the background, which will in turn deny policy makers and practitioners the opportunity to engage with the human aspect and thereby close off a much needed conversation in respect to that.

To be honest, of course, it’s not at all surprising to find this focus in a Labourite document, as we can still hear Harold Wilson echoing down the decades from 1963 as he crowed about how his government would be focused on the “white heat of technology“.

Statism

As mentioned earlier, Labour loves to occupy the state and use it as an instrument for change. Unfortunately, this reliance on an unwieldy and unyielding governmental structure to affect the socio-economic change that this party embraces programmatically removes the potential for a meaningful movement to come together to pursue a necessary transformation.

This is why we see citizens being corralled into offering responses to structured questions rather than being offered the opportunity to be a constant and influential voice in the political discourse of a party seeking to improve and enhance the lives of the population. One might not unreasonably accuse Labour of ventriloquism in respect to the formalised “consultation” about which it crows in the 10 year plan document.

Managerialism

The voice of Wilson can certainly be heard clearly in this paper…but equally we can discern the dreary neoliberalism of Tony Blair therein. This is especially potent when it is closely aligned with the state, as discussed above. For example, at one point we find a grandiloquent assertion that ‘Our reforms will push power out to places, providers and patients…’, but 10 paragraphs above sits a statement as to how this government will address issues of obesity in society, which uses the words “restrict”, “ban”, “levy”, and “mandatory” (p6). There is a commitment in principle to push out power…but a clear sense of retaining power at the centre, and hence potentially taking it back at a whim.

Blair’s presence – and an indication of his dismal legacy in terms of public sector governance – is extremely apparent in a statement in the document that does not even attempt to deny it’s adherence to the ideology of New Public Management (NPM), which – in its Thatcherite/Blairite manifestation – was all about metrics-led consumerism: ‘Specifically, we will…publish easy-to-understand league tables, starting this summer, that rank providers against key quality indicators.’ (p7).

The way in which this sort of oversight encourages the gaming of the system has often been raised. And at least one author has persuasively argued that it is possible to make the case that the predominance of New Public Management led to a decline in compassion across the service. NPM has also facilitated the overall dominance of managerialism across the NHS, which means that serious conversations about what it should mean theoretically and in actual practice to manage or lead some aspect of health and social care are simply denied room wherein reflection, inquiry and dialogue around this challenging and important topic might take place.

Structuralist not Systemic

For some time now, there has been a sensible attempt to try and foreground systems thinking as a means by which to encourage all involved in weaving together meaningful health and social care cover for the whole population. This tends towards a focus on the concept of the Complex Adaptive System (CAS), which supports policy makers, practitioners, and managers to think differently about the terrain in which they find themselves; how agencies and people might come together in order to address challenges and realise ambitions for socialised medicine in this country; and how issues of ill-health might be approached more obliquely in order to shift our focus from conditions to situations.

In the summary of the 10 Year Plan, we see yet again the dominant discourse that the NHS should be structurally at the centre of a revised health and social care provision – and is actively promoted as the motor for that change, even though there are cultural disparities between its monolithic, hierarchical, and command-and-control structure and the way in which agencies alongside whom it should be working conduct themselves. The fact remains that the Labourite NHS has a significant democratic deficit, in contrast to its local authority partners…and yet the former is constantly put in the driving seat. For instance, in the document it is stated that the government will ‘…create a new opportunity for the very best [Foundation Trusts] to hold the whole health budget for a defined local population as an integrated health organisation (IHO).’ (p7)

This document – although possibly not the heftier and unabridged version of the plan – offers very limited systems thinking. It is no panacea, of course, but it does challenge everyone involved in health and social care to think differently about the demands that exist in regard to the well-being of our populations, inviting them in many instances to go back to first principles but also to move beyond privileging the point at which they are providing a service to arrive at a place where greater relevance is accorded as to how the various agencies interact.

Familiar

I am extremely aware of the tendency to look at new suggestions and to slip into a condemnation of them as repetitions from the past. Given my age, if I listen to contemporary music, I far too often find myself thinking, “That’s a straight rip off of so-and-so!”, with the latter being filled with the name of an artiste or a band that was important to me in my youth. As soon as that happens, I call a halt – and set aside that initial observation, so as to go back to the new track and focus exclusively on it rather than simply condemn it as an unimaginative copy of something from the past.

I can also experience this kind of effect in terms of the passing of time in respect to that which is promoted as novel when it comes to organisational life. Again, it is important to suspend the visceral reaction in favour of a more thoughtful engagement with what I might have seen in the past and that with which I am confronted at this time.

However, it is also the case that my experience – and that of others – will often demonstrate that ideas being promoted as new are instead clumsy retreads from the past. (This reflects our unhelpful cultural fixation on novelty, when innovation is so often exclusively focused on the supposed appearance of brand new ideas when we should concern ourselves with the emergence of previous perspectives that can be expressed and viewed differently – or which might enjoy greater currency as a result of the passage of time and the organic change that arises from this.)

All of which means that the so-called new ideas that emerge from the past should certainly not automatically be rejected. That said, their provenance is something that needs to be acknowledged in order to find ways in which such initiatives can be offered the best possible opportunity to be successful and produce positive outcomes.

In this regard, as I read the 10 Year Plan summary, I was initially intrigued by the commitment to offer NHS staff access to career coaching. I was then thrown back to the time when I worked for the NHS University. NHSU was an effort to establish a corporate university for the health service, which encompassed everything from induction into a national corporation, continuing professional development, and lifelong learning. (The latter should give the lie to the fact that this too was a Blairite initiative, arising out of his assertion that it was all about “education, education, education”).

An important element of this sizeable investment in a new organisation to support staff development across the entire NHS was the provision of a professional Information, Advice and Guidance service (IAG), by which was meant active support to health service people in terms of planning their careers and accessing opportunities that would support their progression. All of which means that the blithe assertion that people should access this coaching needs to be carefully considered alongside previous experience in this regard – and provision be tailored on actual present need and past experience.

Militaristic

Finally, the NHS fascination with the military resurfaces in this document. The unimaginative and unambitious report on NHS leadership produced by a superannuated soldier continues to define how development is thought about in this regard. Hence, we find the 10 Year Plan excitedly talking about setting up its own version of Sandhurst, instead of offering an invitation for an ongoing and meaningful debate as to what it might actually mean to try and run health care provision in the contemporary context where the focus will be on encouraging and supporting its people and – rather than only obeying orders – engaging with the organisational circumstances in a way that emphasises criticality, reflexivity and the development of an ethical self.

Where does all of this leave us?

It seems to suggest an urgent need for support to be put in place to assist with the emergence of a meaningful social movement focused on fresh thinking and new perspectives on socialised medicine. There is an unpleasant reek of Stalinism attached to the idea of a “10 year plan”. Instead, the document should be used to encourage a consultation that goes beyond the call-and-response of standard public engagement and foregrounds the vital importance of people finding their voice – and of those voices actually being heard, rather than merely offering a sound bed for the dominant voices at the top of the pyramid.