Unreliable reflections on Kevin Flinn’s ‘Organisational Development in Practice – a complexity approach’ (Routledge, 2026)

John Higgins, January 2026

This book raises its flag and stands its ground in opposition to the managerial instrumentalism of organisational and community life, which has ‘reduc[ed] ethical questions in the workplace to matters of efficiency and effectiveness’ (P. ix).

It calls out as absurd much of what passes as common sense, that meaning making can be planned, that collective sense making can be short-circuited, that by mandating a single perspective on the myriad nature of truth, it becomes universal.

Kevin argues that the often presented as impractical/other worldly philosophy of complexity ‘is a… more reality congruent reflection of the patterns of human interaction that have been hidden by artifice and abstraction’ (P. 43). It brings to our attention what gets disappeared by the approved of and seductive appeal of tidied up models and frameworks by:

‘… acknowledging the complexities, [inter-]dependencies and uncertainties of day-to-day life in organisations, the differences we bring, and the relations of power (inclusion and exclusion) that we are all co-creating – influencing whilst simultaneously being influenced’ (P. 114)

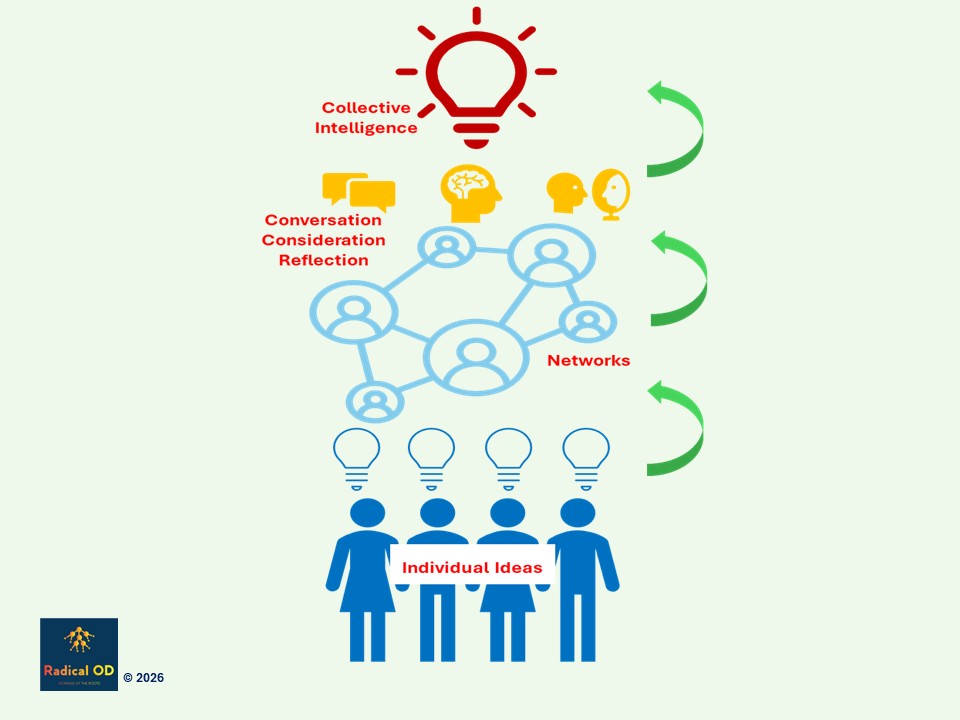

In his work he isn’t acting as an executive handmaiden; he is looking to mobilise people’s collective intelligence in the service of some yet to be known collective endeavour, under conditions which cannot be prescribed for. Let me highlight this through three quotes:

- Kevin and his intention for his work… ‘helping communities of people to develop their capacities for organising is a useful description of what I find myself doing’ (P. 5)

- Kevin on collective thinking and intelligence… ‘Practical judgement is not about consensus, or compromise, it’s about collective thinking, collaboration and mature citizenship… opening up spaces [to] explore conflicting ideologies, and hold each other to account’ (P. 91/2)

- Kevin on the conditions for this work… ‘Psychological safety is… about convening a space where we can think collectively about the fact that we are not’ (P. 22)

And as I try to appreciate and point you towards what to me is a profoundly more sensible and pragmatic approach to organisational development and management, I am walking into the paradox of doing the work that only you can do – or rather only we can do together i.e. make sense of a complexity approach in the unique circumstances of our lives and of those around us, while at the same time accepting that I am at best an unreliable narrator when it comes to promoting Kevin’s work:

‘As OD [Organisational Development] practitioners, we are often asked to summarise… I argue that as soon as we do this, we become unreliable narrators… we do have a choice about whether we become witting or unwitting unreliable narrators’ (P. 17).

For me, his work has defamiliarized once again my assumptions about how I go about making meaning in my life, how I look to work with others as they go about making meaning, and my persistent desire to over-reach and make sense of what is not within my or anyone else’s gift, to make sense of reality on behalf of others.

This desire is part of a deeply entrenched cultural norm in every field of organisational management, leadership, development and practice, which Kevin seeks to bring to our intention so we can consciously do something different:

- Kevin on knowing the world differently… ‘Our job, as OD practitioners [is] to defamiliarize the ordinary… to produce oddness’ (P. 118)

- Kevin’s ambition for the reader of his work… ‘I’m looking to provide the reader with the opportunity of finding their own truth, truth for them, for now’ (P. 156)

As someone who has chosen to promote Kevin’s book as an insightful challenge to organisational norms, I am trying to do what can feel like an impossible job – which is one I should maybe stop trying to do… I write into and engage/research within a world of work addicted to instrumental, reductive, short-circuited meaning making. And I look at Kevin’s advocacy, his insight that ‘we… find more reality… in fictional accounts of everyday life than we will in the case studies contained in conventional literature on OD’ (P. 41), and his dwelling with the meaning we can all find in Joyce’s Ulysses.

And I feel over-whelmed by the seeming impossibility of connecting these incommensurable worlds, before coming up for air and realising that this sense of being overwhelmed is all wrapped up with my belief in my responsibility for individually and heroically bridging the gap between the philosophy of the instrumental and that of the unknowable emergent, whereas what Kevin is advocating dissolves this experience by relocating it into a different social context:

‘A complexity approach… means letting go of the notion that we can preplan what will happen between us’ (P. 133)

* * *

John is a researcher and author around many aspects of organisational voice and meaning making. He is Research Director at The Right Conversation

Thank you for the kind review, John. And thank you, Mark, for acting as host.

Kevin

https://www.routledge.com/Organisational-Development-in-Practice-A-Complexity-Approach/Flinn/p/book/9781032447124

LikeLike